During the 19thcentury, a series of duels were fought by Jews on grounds of anti-Semitism. For some parts of society, it wasn’t clear if you should even accept a challenge to duel from a Jew. But for the Jews, duelling would come to play an important part in the emergence of Zionism and in gaining a sense of pride and honour.

In the 1890s, Theodore Herzl, the founder of modern political Zionism, mentioned to his friend Baron Leitenberger that he thought about challenging some well-known anti-Semites to a duel; either Baron von Liechtenstein, Georg von Schönerer or Karl Lüger. If he were killed, he said, it would cause a public outcry, and if he won, he would express his sorrow in the trial. Perhaps, he mused, he would even be offered — and decline — a seat in the Parliament. He said this was more a dream than an idea, but it was a dream for good reason.[1]

Long before becoming an advocate for a Jewish state in Argentine or Palestine, Herzl was a Germanophile and a great admirer of Europe’s peoples and cultures. In his youth, he was a member of a German nationalist fraternity before leaving it in protest of anti-Semitism. Maybe it was partly wounded pride that made him fantasize about duelling, but it was also an answer to a question that haunted him through much of his life: how can Jews become accepted in Europe and also transform themselves?

Herzl wasn’t clear on the way forward for the Jews in Europe. He loved Germany, Austria and Hungary and wanted Jews to become more like Central Europeans. At one point, he struggled with ideas of whether the answer was to convert to Catholicism. Maybe, he thought, that would make Jews more well-respected and assimilated into the European societies. He also felt that Jews were too timid, too hunkered down after centuries of oppression. Through German influence, they could perhaps transform themselves and become a Kulturvolk?[2]

This is where duelling comes in. In one blow, Jews could demonstrate their worth, stand up against their detractors, and prove to themselves and to the world that they were honourable. Duelling was, after all, the highest possible form of upholding personal honour and Herzl himself was an avid practitioner of fencing. He wrote to Leitenberg: “Half a dozen duels would raise immensely the social standing of the Jews.”

The killing of Captain Armand Mayer

Theodore Herzl would not fight a duel, but he did write about just such a duel in Neue Freie Presse, between Captain Armand Mayer and Marquis Amédée de Morès.

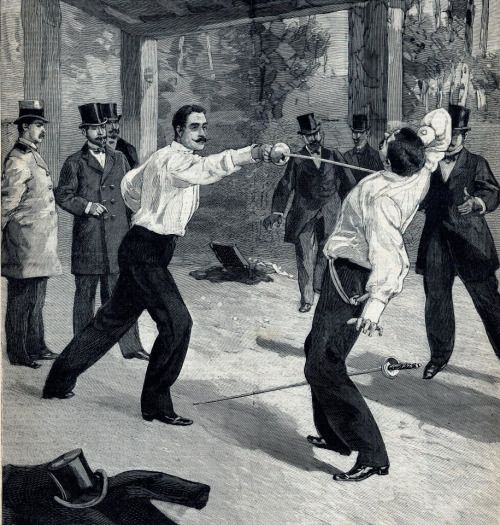

Morès was an associate of the writer and politician, Édouard Drumont, who wanted all Jews to be excluded from society. The affair between de Morès and Mayer was the result of accusations of treason against Jewish officers in Drumont’s anti-Semitic newspaper La Libre Parole. This had led to a duel between him and André Crémieu-Foa, a Jewish officer. Drumont was slightly injured to the arm in the duel. The actual writer of the article, M. de Lamase, then challenged Crémieu-Foa, since it was he who had written the piece. This second duel resulted in four bullets missing their marks. At this point, the seconds of the first duel, Captain Armand Mayer and Marquis Amédée de Morès also agreed to risk their lives for honour’s sake.

The duel was fought on Île de la Grande Jatte and it was a devastatingly quick affair. Mayer had an injured arm but refused to back down. Still, it hampered his performance significantly, and only three seconds in, he received a thrust to the chest. Morès’ saber penetrated his lung and was stopped only by his spine. The two men shook hands, and Mayer was taken to hospital, where he died later that afternoon.

A spectacular irony of the duel is that one of the witnesses who testified against Morés in the inevitable trial was Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. He has been accused of being the actual spy in the notorious Dreyfus affair, which would start just two years after the duel and draw in much of the European intellectual elite.

France was disgusted with the blatant anti-Semitism

After his death, Armand Mayer was celebrated as a hero and an ideal of French nationalism. His killing became a reproach to anti-Semitism as a cause of division in the country. Since his family had left Alsace during the German occupation, he was hailed as a symbol of the Jewish devotion to the nation, and between 20,000 and 100,000 Parisians lined the streets for his funeral cortège. In Parliament, the Minister of War spoke up for the Jews, and newspapers were filled with condemnations of anti-Semitism. The whole affair stood out as a big win for the assimilation of Jews into the nations of Europe, and it was clearly a big defeat for anti-Semitism.

As a little side note to this, it may interest the reader that de Morès, at one point, also challenged the American President Roosevelt[3]to a duel over a dispute relating to a failed cattle business. Roosevelt managed to avoid the duel, and Morès would meet a violent fate, as he was killed by Tuaregs in North Africa when he was trying to establish a Franco-Islamic alliance in 1896.

“They do not yet know that the Jews have learned well the wielding of the sword”

In Hungary, Herzl’s home country, duelling anti-Semites grew to a trend. Thirteen per cent of those convicted of duelling in 1888 were Jewish; during the interwar period, that percentage rose to 50%.[4] Duelling had become a way to prove Jewish courage so that no one could say they were less honourable than Christians.

A splendid example of this attitude was Lajos Szabolcsi, the Editor-in-Chief of a Jewish newspaper called Egyenloseg (Equality). In 1895 he wrote: “The epidemic of Jew-hatred has to be combated by duels. Today our Jewish youth will convince the Jew-haters of our right only with the sword.” “The extremists among the anti-Semites come from the rural areas. They do not know yet that the Jews have learned well the wielding of the sword.” Much like Herzl, Szabolcsi was also clear that duelling was a way to turn the Jews into Hungarian patriots, which would help them gain acceptance.

Duelling became extremely popular. One man, Pál Schlesinger, allegedly fought 100 duels to defend Jewish honour. A newspaper reported that as late as November 1927, at least 40 duels were scheduled that week alone between Jewish students and anti-Semites[5]. The trend spread, and Jewish students in Hungarian universities, particularly Debrecen, began regularly challenging their detractors to duels.

For many Jews in Hungary, duelling was a way to transform and prove themselves and show that they were as worthy as those that the Hungarian Noble class referred to as Úriember, meaning a gentleman of “scrupulous propriety, courtesy, decency, honor”2. The gentiles who were challenged by Jews had to make a choice; they could accept, which also meant recognizing that the rival had equal status. Or they could refuse, which opened them up to disgrace. As a strategy for acceptance, duelling was a highly effective method.

Olympic fencing medals

The culture of fencing also grew into a popular sport in the Jewish communities. In 1906, the Zionist leader Lajos Dömény founded the Jewish Fencing and Athletic Club. Siegfried Flesch, an Austrian Jew, won a bronze medal in saber at the 1900 Summer Olympics, and that was the first of 90 Olympic medals, 47 of them gold, that have been won by Jewish fencers.[6] Jewish athletes have won more fencing medals than medals in any other sport.

In the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Jewish fencers took home four of Germany’s eight medals in fencing. The Jewish German female fencer, Helene Mayer, became a front for the regime to legitimize the Olympics being held in Berlin and in a famous photograph, she is seen doing the Nazi salute. What is spectacular is that all three women on the podium were Jewish. Mayer herself later met with Hitler and referred to him as “a cute little man.”

It would take until the 60s before Fencing caught on in Israel, however. The Jewish fencer and writer Yehuda Carmi writes in “Sport Immigration” how in 1965, there were only 25 fencers in Israel. In four years, their numbers grew to around 3,000 fencers in 200 different clubs. Carmi asked himself why they stuck with an “elitist, unpopular sport” even after they came to the Levant. The reason was that for Jewish immigrants, fencing wasn’t about sports. It was part of their culture.

Sources:

[1]Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism, Jacques Kornberg, 1993

[2]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodor_Herzl

[3]http://www.historynet.com/one-deadly-dude-marquis-de-mores.htm

[4]The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology, Raphael Patai, 1996

[5]https://www.bh.org.il/the-dueling-jews-of-budapest/

[6]https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/.premium-the-curious-history-of-jewish-fencers-1.5317612