Historical European Martial Arts have come a long way over the last two decades. From a small group of enthusiasts to becoming a proper sport, having federations, qualified instructors and a network of academics. But what are the parts of the sum that is HEMA?

The great endeavor of historical fencers is to recreate the lost martial arts of Europe. There are some living traditions too, and the hope is to breathe new life into them as well and make sure they are preserved and remain living.

But what defines HEMA and what is it based on? Here are four pillars on which HEMA stands. Some of these HEMA has in common with other historically oriented martial arts, others are unique specifically to the recreation of our European martial traditions.

The first pillar: Scholarly work

For a very long time, fencing manuals were overlooked by academia. Since the decline of interest in historical fencing after the late 19thcentury, the extensive amount of martial material that has been handed down to us through the centuries was simply ignored. There were of course collectors and people with some special interest, but they were few in numbers and the material wasn’t very well understood. Not even by the rare academics who took interest in the sources.

Since the late 1990s, however, there has been a lot of work to find, transcribe and translate these sources. Beyond that, the academic field can also be said to include practical tests, research on history and adjacent subjects such as metallurgy, psychology or trauma caused by violence.

The second pillar: training and teaching

Of course, it wouldn’t be a martial art if we didn’t train after the manuals. To physically understand and interpret the sources and put them into real applicable techniques is naturally a big part of recreating these lost arts. Beyond that, there is also teaching methodology, drills, cutting, physical and mental training, and much more that is connected to the application of the sources. All of this, can be said to be part of the training and teaching part of HEMA.

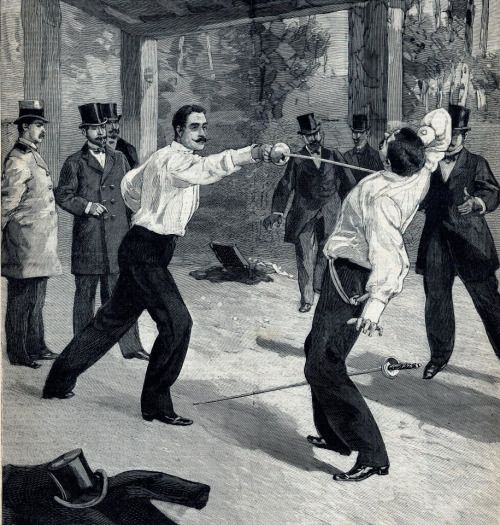

The third pillar: Competitions

In the beginning, competitions were rare and not very professional. They were also often overlooked and ignored, and there was a fear of HEMA becoming sportified. But in the end, competitions are necessary to test techniques against uncooperative opponents and they have proved to be essential in fostering good martial artists and to test ideas. Today, competitions are a major part of many events and probably what draws most attention.

The fourth pillar: Culture

Historical martial arts cannot be fully understood without the contexts in which they were practiced. This includes the ideals of for example chivalry and honour, but also whole range of practices which are tied into the historical martial traditions; like sword dancing, symbols, habits, music, ceremonies and rituals. To recreate these cultures and make them part of the living traditions of HEMA is an important part of the puzzle. They teach fencers about history and what it meant to live by the sword. And just as historical fencers must be dedicated to reviving and embodying the martial skills, many choose to revive and embody aspects of the martial cultures of the past.

Anders, again – great article! Can you share the source of the sword-dancing picture? Origins and age? What is known about the cultural significance of that dance? Are there similar renderings or sources? Best regards, Frank

Hi, here’s a text, which I think is about it. But unfortunately I don’t speak the language. It’s just one of many images which I have saved on sword dancing.

https://www.tornaveu.cat/reportatge/2934/torna-el-ball-despases-a-cervera-300-anys-despres

Sword dancing has survived in several places, but have mostly lost its original martial connection. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sword_dance

There’s a book about it, but the author’s name escapes me right now. I’ll get back to you on that.