China has been building its HEMA scene for over a decade, and it’s showing real depth. I spent a week in Shanghai with SHMA (Shanghai Historical Martial Arts), teaching a two-day German longsword workshop, helping judge a two-day tournament, and training. And hanging out with the club of course. What I saw was an energised community with momentum and eagerness to excel.

As we were driving through this city of twenty-six million inhabitants, passing the countless rows of tall apartment buildings, I couldn’t help but think what a peculiar journey historical fencing has been for me. Could I have imagined, when I started fencing at 13, that my love for swords would one day take me around the world to teach? I doubt it. Yet here we are. Even more strangely, to see the things you helped develop, emerge in a setting on the other side of the planet.

SHMA is China’s biggest and oldest historical fencing club

SHMA is, by any standard, a serious operation. They train in a large hall packed with equipment, with classes running seven nights a week and nine dedicated instructors. With roughly 300 active members, they already rival or surpass most European clubs.

But it wasn’t always like this, of course. Their founder, Jimmy Chen (陈佳, Chen Jia), started ten years ago with a handful of friends training outdoors under a bridge. They weren’t doing historical fencing, but sword fighting, and it wouldn’t change until students who had been to the US and Europe came back to China after finishing their education. They shared their experiences of HEMA and inspired Jimmy and the others to switch focus towards historical European arts, and to build a real club in a proper hall.

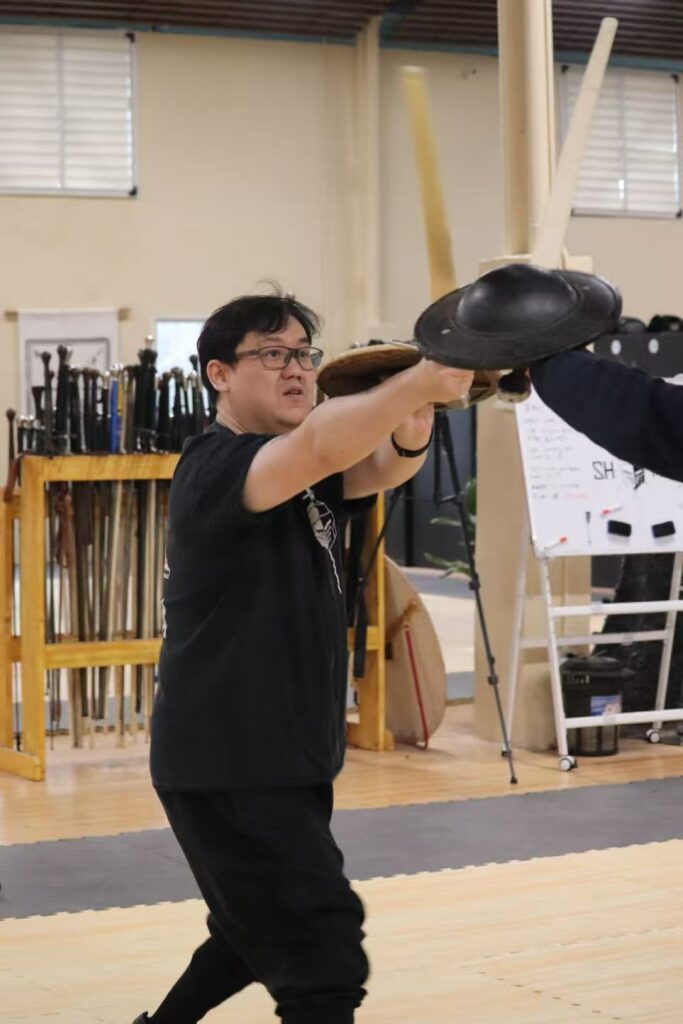

But unlike most clubs, SHMA doesn’t limit itself to Western martial arts. They also train Chinese historical martial arts with weapons like the changdao (Chinese long knife) and daqiang (Chinese spear). This mix of arts also means a fusion of approaches, where the club competes in both HEMA and Chinese arts using the Nordic ruleset. In fact, during the two-day competition, one of the fencers who won no less than three gold medals, Sheng Hongyuan (盛弘源), better known by his nickname Spider (蜘蛛), is a self-taught Chinese martial arts practitioner.

High standard of competition

The day after my arrival, it was time for the tournament. It featured longsword, sabre, and dao, with fighters from Shanghai, Nanjing, and a few from further inland. The event was small, with around 30–50 competitors, but the standard was impressive. In tournaments like these, the best way to evaluate the level is not to look at the best fencers, but at the pools. And the pool level was quite high by any standard.

The competition ran very smoothly. The judging was consistent, the pacing efficient, and the culture very respectful. No drama, no tantrums, some friendly banter at most. As an organiser, I know to value these things, and it’s generally a result of organisational decisions and clear leadership.

In this case, the organisers reduced the number of judges to two and limited their decision-making by having the referee call point. This sped things up and meant that more people were senior enough to take on the role of point judge. A downside of this was that it left a shorter time for afterblows, which meant many fencers stopped immediately after an exchange. Apart from this, the fencers showcased the systems well, and the judging was better than what you see in most tournaments.

A culture of exchange

I wasn’t the only Westerner present. Among the participants was Tobias Thomé from Bruckenschlag, Germany, who happened to be vacationing in Shanghai. Naturally, he jumped at the opportunity to participate and finished third in sabre.

“I had a great time at SHMA. I was warmly and quickly welcomed — not only was I invited to participate in the tournament on short notice, but they also provided all the necessary equipment. At the tournament, I experienced a wide range of skill levels: from relatively inexperienced beginners to seasoned and capable fencers who could confidently compete at any event in the world. I felt well challenged throughout. Even the beginners showed endurance, determination, and a willingness to fight hard. All of my opponents displayed consistent sportsmanship.”

I also had the good fortune to meet up with an old club mate. Before the pandemic, Andrew (徐晓非) chose Sweden for his university studies because he wanted to train with GHFS. It was just at the time when I was leaving the club, so he mainly trained under Kasper Aase, but we did have some interaction since he’s also responsible for translating some of my videos and texts for Chinese audiences. He’s also translating Ringeck to Chinese, the first translation of its kind, I believe. During the event, we had many discussions about the German text and the interpretations as a result.

To me, this summed up the spirit of the whole event: structured, open, and genuinely eager to learn from one another.

The Workshop – Longsword as System

My workshop focused on the German longsword, but we used it as a vehicle for something broader: how to train it effectively. We worked through the core actions of Liechtenauer’s lessons with the various techniques coming from the cuts, but also with an emphasis on pedagogy, connecting drills and moving from isolated exercises to free sparring and building skill sets.

I did not know what to expect beforehand and had prepared exercises for different levels, but it was soon clear to me that the technical base of the participants was solid. We quickly went through most of the exercises, putting the system together into complex drills. This is something extremely positive for someone doing a workshop because it means you can get into more challenging ground quickly and can focus on helping fencers look at things from tactical perspectives rather than drilling basics.

What also stood out was the great sense of community at the club. Jimmy has created a home away from home, where people come to hang out and where new students show up for private lessons, older students cook and eat together, relax on beanbag chairs, and joke and socialise.

Structured ambition to learn and excel

Chinese clubs like SHMA are systematic in inviting foreign instructors. Previously, they’ve hosted Axel Pettersson, Lee Smith, Arto Fama, and Ties Kool, among others. It’s a good approach to bridge the gap to Europe, since the Chinese HEMA scene remains partly isolated. The Great Firewall blocks most Western media platforms and there’s naturally a language barrier, where some Chinese fencers lack the language skills to participate freely in English-speaking groups. But in the end, the real blind spot is in the West, where hardly anyone speaks Chinese or accesses their forums.

Another interesting thing is how people are attracted to HEMA in China. In the West, many people come to us through a cultural connection to what the sword represents, often expressed through pop-cultural phenomena. In China, this seems to be even more pronounced, with frequent references to The Witcher, anime, and similar influences. Combined with an agnostic approach that blends Eastern and Western arts, it creates a distinctive environment for HEMA, not unlike what we see in the United States, a culture also one step removed from the European context.

This approach was cited as one of the reasons for HEMA’s rapid growth in China by my interpreter, Cloud. SHMA’s intention is to draw people in through familiar influences, then guide them toward a more canonical and historically faithful approach to fencing. Within the club, this is sometimes discussed in terms of sportive versus cultural: sportive referring to fencing approached as a modern, competitive discipline, and cultural referring to training grounded in the transmitted arts described in the historical sources.

Chinese fencing on the rise

There’s no doubt that if the Chinese scene continues at this pace, we’ll soon start meeting Chinese names in international brackets, and eventually in finals. At least, that’s Tobias’s conclusion.

“I have not yet seen fencing at the absolute world-class level here, but in my view, they are not far from it. The fighting spirit is definitely there, though the focus on defensive fencing and a quick withdrawal after landing a hit is sometimes neglected in favour of hard exchanges. If they refine their training in that regard while maintaining their own unique perspective on historical fencing, I have no doubt that many of the world’s top historical fencers in the near future will be Chinese,” he said afterwards.

Driving back through the same endless rows of apartments at the end of the week, I thought again about this journey. Fencing has carried me far — but what’s happening here in China suggests that its next great chapter has only just begun.