– An Adventurer Goldsmith in Rennaissance Italy

Renaissance Italy was a place where beauty and blood flowed in the same veins. Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571) embodied both. Master goldsmith, sculptor, musician, soldier, and memoirist, he dictated his autobiography La Vita between 1558 and 1566 while supposedly “recovering” from yet another brawl. The book is not a polite recollection. It is a blood-soaked boast, written by a man who saw every killing as justified, every insult as a death sentence, and himself as the greatest artist who ever lived. For the historical fencer, it’s a goldmine of insights into the world of Renaissance Italy.

“Such grace worth beauty be through me displayed

That few can rival, none surpass me quite.”

Cellini was a man larger than life. He opens the book by claiming that Florence itself was named after an ancestor of his—Fiorino of Cellino—because Julius Caesar liked the man’s flower-filled camp. From that moment on, every triumph, every narrow escape, every papal pardon is presented as further proof that he is not merely talented, but destined for greatness. When you read La Vita today it’s sometimes hard not to laugh at the sheer audacity of the man. And you can’t help feeling that the people around him—popes, patrons, rivals, even his own apprentices—were mostly right about him. The man was an absolute menace. And what you get from him is a first-hand account of violence, honour, and temperament in the same cultural world that produced the great Renaissance fencing treatises.

The Rise of a Hot-Headed Goldsmith – Florence, c.1523

Born in Florence on All Saints’ Day 1500, Cellini was the son of a musician who wanted his son to master the flute. Instead, the boy was drawn to metalwork. By his late teens he was already working as a goldsmith, supporting his family through his craft, but his technical promise was paired with a temper that has come to define his reputation.

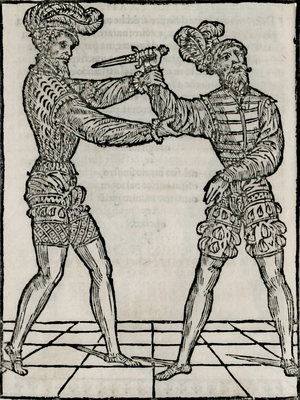

One of the earliest incidents, happened in 1523 when a feud with the Guasconti family erupted into violence. The quarrel began in the street, where Gherardo Guasconti deliberately shoved a passing load of bricks into Cellini, injuring him. Cellini responded instantly, slapping Gherardo unconscious, while holding a knife in hand (which was a crime). The Guascontis ran to the magistrates and accused him of attacking them in their shop with a sword. He was summoned before the council of the Eight (I Otto). Thanks to the intervention of Prinzivalle della Stufa, the sentence was reduced to a humiliating fine: four measures of flour to be given as alms.

The insult burned deeper than the punishment. When a cousin refused to stand bail for him, Cellini describes himself as “turning wholly to evil.” He ran to his shop, seized a dagger—a pugnale (the same term is used for a dagger by Marozzo)—and stormed the Guasconti household, where the family were eating together. He stabbed Gherardo in the chest, driving the weapon through doublet and jerkin. “I felt my hand go in, and heard the clothes tear,” he writes, believing he had killed him.

The room collapsed into panic. Father, mother, and sisters fell to their knees screaming for mercy. Cellini spared them and charged downstairs into the street, where more than a dozen members of the household attacked him with iron tools: hammers, an anvil (most likely the smaller goldsmith version), a shovel, pipes, cudgels. He describes raging through them “like a mad bull,” slashing with the dagger while blows rained down on all sides. Miraculously, no one was killed.

The authorities responded with extraordinary severity. A ban was issued declaring him an outlaw; anyone who sheltered him would face punishment. Armed by his father with a sword and coat of mail and disguised as a friar, Cellini fled Florence by night, beginning a pattern that would define his early life: violence, escape, and reinvention.

The Siege of Castel Sant’Angelo

By late 1523, Cellini arrived in Rome as a fugitive, his flight triggered by the Guasconti death sentence and a lingering sodomy charge, the first of several that would dog his career. In this he followed a distinctly Florentine pattern: accusations of sodomy were so common in the city that they became a social hazard for ambitious young men. Both Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo had faced similar charges, and like Cellini, Michelangelo would also leave Florence for Rome under their shadow. It should be mentioned, that sodomy did not mean just homosexuality, but included specific sexual acts with women as well. Elsewhere in Europe, the phenomenon was cynically labelled the “Florentine Vice”.

Yet, while his predecessors met these charges with tortured silence or poetic despair, Cellini met them with characteristic defiance. Years later, when his rival Baccio Bandinelli branded him a “sodomite” in the duke’s court, Cellini didn’t flinch. Instead, he mocked his accuser and joked that he only wished he were “worthy” of such a “noble art” practised by the gods of Olympus and the greatest emperors of history.

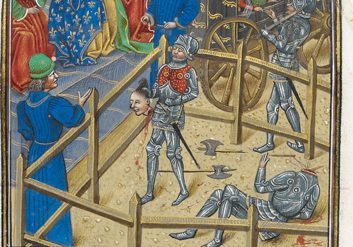

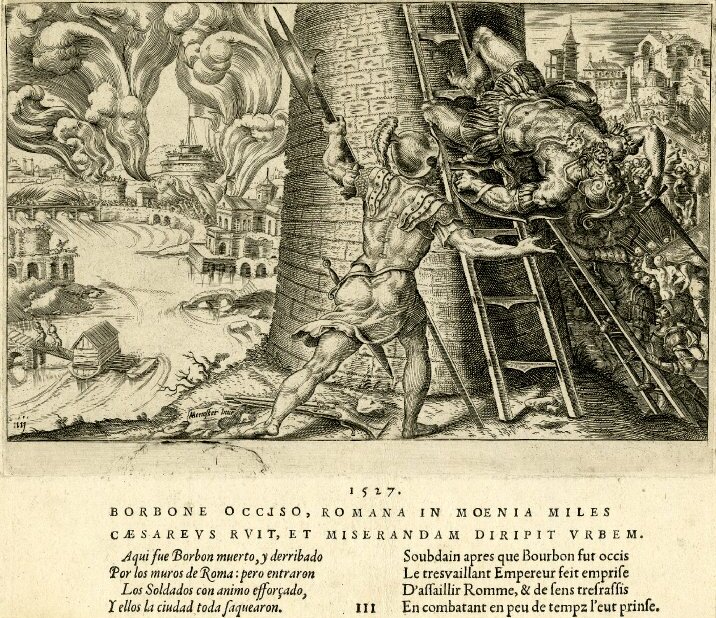

In Rome, Pope Clement VII, a fellow Florentine and a Medici, took a liking to the young goldsmith’s fiery spirit. Cellini was soon entrusted with the minting of papal coins, seals, and intricate jewellery. Then came the catastrophe that would define his legend. In 1527, the unpaid, mutinous army of Emperor Charles V—roughly 20,000 strong, including 14,000 German Landsknechte fuelled by Lutheran zeal and a vitriolic hatred for “popish idolatry” and the Papacy itself—marched on the Eternal City. To these soldiers, Rome was not the holy city, but the “Babylon of the Apocalypse,” and Pope Clement VII was the Antichrist. They even dressed up a prostitute as the pope and placed her on the throne of Saint Peter.

On 6 May, the walls were breached under a thick fog. While the Swiss Guard were being slaughtered on the steps of St Peter’s to buy the Pope time to flee through the Passetto di Borgo, Cellini retreated to the battlements of Castel Sant’Angelo. Here, the goldsmith reinvented himself as an artillerist. In his autobiography, he insists he was as naturally drawn to soldiering as to metalwork. He famously claims it was his harquebus shot that killed the Constable of Bourbon, the Imperial commander, during the initial assault. While historians confirm Bourbon fell to a marksman’s bullet, they are naturally skeptical that it belonged to Cellini.

His most cinematic boast involves a Spanish colonel in rose-coloured silk, who wore his sword in an “arrogant” Spanish fashion. Cellini seized a massive gerfalcon cannon, which was a long-barreled precision piece, loaded it with a mix of fine and coarse powder, and fired. He describes with grisly relish how the shot smashed the man’s sword and cut him “in two pieces.” He says Pope Clement, watching the carnage, made the sign of the cross over Cellini, and that he was granted full absolution for every killing—past, present, and future—committed in the Church’s service.

The Sack was an atrocity of unparalleled scale, but for Cellini, it was also a practical workshop. Beyond killing and soldiering, he spent much of the siege performing a tragic alchemy: melting down the golden papal tiaras and heavy regalia to anonymous ingots to hide the wealth from looters. Something which would get him in good standing with the pope, but also in trouble later on.

The Restorative Kill: Rome, 1529

The dust of the Great Sack had barely settled when Cellini’s brother, Cecchino, was shot in the leg in a street skirmish by a city guardsman. Cecchino died of his wounds, and for Benvenuto, the clock of the vendetta began to tick.

This was not the first time one of his brothers was involved in street violence. In his youth in Florence, he had already stood over another brother, 14 yers old at the time, struck down in a streetfight that began as a duel and ended as mob assault.

“…he came to duel with a young fellow of twenty or thereabouts. They both had swords; and my brother dealt so valiantly that, after having badly wounded him, he was upon the point of following up his advantage. There was a great crowd of people present, among whom were many of the adversary’s kinsfolk… they put hand to their slings, a stone from one of which hit my poor brother in the head. … I ran up at once, seized his sword, and stood in front of him, bearing the brunt of several rapiers and a shower of stones. I never left his side until some brave soldiers came from the gate San Gallo and rescued me from the raging crowd; they marvelled much, the while, to find such valour in so young a boy.”

Unlike Cecchino, the younger brother survived, and the authorities exiled the attackers, closing the matter legally. But this time it was different, honour had to be restored.

It has to be understood that honour in the Renaissance was the hard currency of social existence. It functioned within a system of legal pluralism where the state did not hold a monopoly on justice. Authority was shared between magistrates and the rigid, unwritten laws of the family. In this landscape, a man’s onore determined his creditworthiness and his safety. When Cecchino was killed, the Cellini family was socially liquidated. To leave the death unanswered was to signal to all of Rome that the Cellinis were broken men who could be robbed or insulted with impunity. Revenge was the mechanism that re-capitalised the family’s standing.

Cellini stalked the musketeer who had shot his brother, eventually cornering him at night near the man’s home. Again, he chose the pugnale, and struck from behind. He describes the anatomical physics of the kill in detail:

“I aimed at the point where the neck joins the shoulder… I struck him such a violent blow that, though I had only meant to kill him, the dagger went in so deep that I could not pull it out. For the dagger had entered the large vertebrae of the neck, and the force of the blow was so great that the fellow fell like a log, and could not even utter a sound.”

The aftermath reveals the peak of Cellini’s political credit. Having melted the papal gold and defended the walls in 1527, he had earned a surplus of favour that effectively paid for this blood debt. In a city where the state shared its authority with the family, the Pope’s reaction was not one of moral outrage but of pragmatic protection. In La Vita, Cellini says the Pope gave him a terrible look, but soon moved on to other matters.

“When we reached the presence, the Pope cast so menacing a glance towards me, that the mere look of his eyes made me tremble. Afterwards, upon examining my work his countenance cleared, and he began to praise me beyond measure, saying that I had done a vast amount in a short time. Then, looking me straight in the face, he added: “Now that you are cured, Benvenuto, take heed how you live.” I, who understood his meaning, promised that I would.”

It was an implicit admission that for a man of Cellini’s importance, the private logic of vendetta could override the public law of the city.

The Limits of Impunity: The Road to Prison, 1538

This system of honour justice was never a clean-cut set of rules; it was a high-stakes social tightrope. While the vendetta was a recognised cultural mechanism, its success depended entirely on a delicate equilibrium of personal standing, alliances, and sovereign favour. Historians like Thomas V. Cohen point out that the Renaissance state was often a “fragile peace” between the central authority of the Pope and the local power of elite families, where violence was allowed only if one had the political “credit” to pay for it. The limit of this system was reached when an individual’s violence began to destabilise the state’s own legitimacy. As long as Clement VII (a Medici) was in power, Cellini was protected by a form of sovereign immunity, viewed by the Pope as an artist whose hands were too valuable to be shackled by common law. But this wasn’t a permanent legal shield; it was a personal lease on life that shifted the moment Clement died in 1534.

Cellini immediately tested this new reality by murdering a rival goldsmith, Pompeo de’ Capitaneis, striking him twice in the neck with a dagger in broad daylight while assuming the old Medici-era immunity would hold.

“I drew a little dagger with a sharpened edge, and breaking the line of his defenders, laid my hands upon his breast so quickly and coolly, that none of them were able to prevent me. Then I aimed to strike him in the face; but fright made him turn his head round; and I stabbed him just beneath the ear. I only gave two blows, for he fell stone dead at the second. I had not meant to kill him; but as the saying goes, knocks are not dealt by measure. With my left hand I plucked back the dagger, and with my right hand drew my sword to defend my life. However, all those bravi ran up to the corpse and took no action against me; so I went back alone through Strada Giulia, considering how best to put myself in safety.”

Initially, he got away with it. When Pompeo’s friends wanted Cellini punished, the new pope answered:

“Know then that men like Benvenuto, unique in their profession, stand above the law.”

However, the political landscape had hardened under the new Pope, Paul III (Alessandro Farnese), and while Cellini secured a temporary pardon, the murder gave the Pope’s son, Pier Luigi Farnese, the leverage needed to dismantle the artist’s autonomy. By 1538, his impunity was gone; as the papacy transitioned from Clement’s personal protection to Paul III’s hardened bureaucracy, Cellini’s political credit hit zero, leaving him vulnerable to a bureaucratic assassination. They did not arrest him for the blood on his hands, which remained culturally and politically messy to prosecute, but instead struck at his integrity through a charge of embezzlement.

Specifically, they accused him of stealing a fortune in papal jewels while melting down the golden regalia during the 1527 Sack of Rome. This was a masterstroke of legal maneuvering because it bypassed the honour defense, was technically plausible given his role at the furnace, and successfully branded him a common thief. He was thrown into the dungeon of Castel Sant’Angelo, the very fortress he had once defended, but this time he was placed in the “Keep”, a place designed to break both the body and the ego.

Theophany of Sammabo

Faced with a system that had finally turned against him, Cellini didn’t beg for mercy; he treated the prison like a technical problem to be solved with a goldsmith’s precision. Using a pair of stolen pliers, he painstakingly removed the hinges from his cell door, covering the gaps with wax and rusted metal filings so the guards wouldn’t notice the tampering. On a moonless night, he manufactured a rope from his bedsheets and began a harrowing descent down the massive outer walls of the fortress. He fell, hit his head on the way down and when he came about realised his leg was broken. He then crawled away, armed with a dagger which he used to defend against some mastiff guard dogs. He comes upon a water-carrier who helps him after being told he broke his leg jumping from a window after a “love adventure”.

He eventually reached the house of a sympathetic Cardinal, but his luck had run out. Recaptured and cast into a deeper, darker pit—the “Sammabo” cell—he found himself in a place of damp walls and absolute shadow. It was here, in the silence of the dungeon with a rotting leg Cellini had a theophany.

Within this suffocating isolation, where his mattress “soaked up water like a sponge” within three days, Cellini’s defiance was transfigured into devotion. Initially driven toward despair, he attempted to take his own life by propping a wooden pole to fall upon his head. Yet, at the moment of impact, he was seized by an invisible power and flung across the cell—an intervention he attributed to his guardian angel. This marked the beginning of his sanctification. While lying in the dark, he was visited by a “marvellous being in the form of a most lovely youth,” and his physical suffering—including the rotting teeth that fell out of his gums without pain—became secondary to his inner light.

The climax occurred on the morning of the 3rd of October 1539. Having prayed to behold the sun one last time, he was granted a celestial vision of the solar sphere, appearing as a “bath of the purest molten gold.” Within this brilliance, he beheld the figures of Christ upon the cross and the Virgin Mary enthroned with her child.

Cellini emerged from Sammabo not as a broken prisoner, but as a man marked by divine favour. He says that from that moment on, a “slight brightness” remained resting on his head—an aureole he described as almost a miracle, visible over his shadow at sunrise.

In Service of King Francis I

Cellini’s release from the Roman dungeons was as much a political manoeuvre as his imprisonment had been. Through the intervention of the Cardinal of Ferrara and the persistent requests of King Francis I, Cellini was finally liberated. In 1540, he journeyed to France to enter the service of the French crown. Leaving behind the volatile legal pluralism of Rome, he sought a new kind of sovereignty in France, one rooted in the absolute patronage of a monarch who viewed him as the ultimate trophy of the Italian Renaissance.

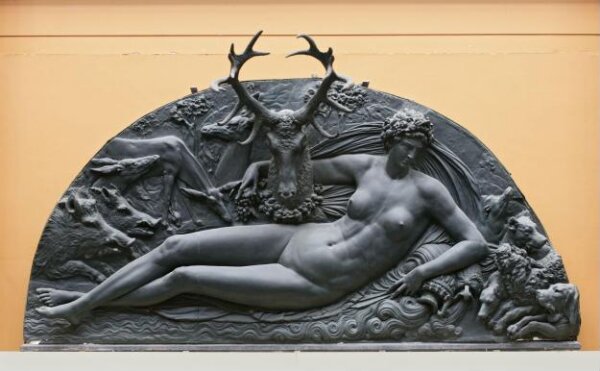

At the court of Fontainebleau, Cellini’s artistic development reached its zenith. From a goldsmith of the Papal mint, he began working on a monumental scale, blending his metallurgical precision with the grandiosity of French Mannerism. It was here that he began the work that would define his French period: the Saliera.

The Private War in the Petit Nesle

Despite his religious experience, nothing really changed in Cellini’s attitude towards violence. Upon arriving in Paris, King Francis I granted him the Petit Nesle, a small castle on the Left Bank, to use as his workshop. The problem was that the property was already occupied by the Provost of Paris, who refused to vacate. Rather than waiting for a legal eviction, Cellini reverted to his habits. He led his men in a literal armed siege of the property, driving the occupants out with swords and pikes.

Once established, he turned the Petit Nesle into a fortified factory. When some high-born friends of the previous owner came to harass him about the legality of his occupancy, Cellini famously told them if they dared draw a blade he would kill them, making it clear that the Petit Nesle was now a private fortress where only the King’s word and Cellini’s steel mattered.

The Conflict with the Duchess and Primaticcio

Cellini soon found that the French court was a labyrinth of intrigue. His primary nemesis was not a fellow artist, but Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, Duchess of Étampes, the King’s influential mistress. The Duchess viewed herself as the supreme patron of the arts at Fontainebleau and was deeply offended by Cellini’s refusal to court her favour, as he preferred to deal directly with the King.

To undermine him, the Duchess championed the Italian painter Francesco Primaticcio (whom Cellini called “Il Bologna”). Cellini, fiercely protective of his commissions, viewed Primaticcio’s rise as a direct threat. In La Vita, he claims the Duchess and Primaticcio conspired to sabotage his designs for the palace’s “Great Doorway”. He responded in character. Rather than appealing to the court, he sought Primaticcio out and told him plainly that if he accepted any commission that had been promised to Cellini, he would kill him “like a dog”. The work went forward under this shadow of violence, and from this volatile atmosphere emerged the monumental Nymph of Fontainebleau.

No Time for Lawyers

While King Francis I may have been amused by Cellini’s seizure of the Petit Nesle, the French legal system was less so. Cellini soon found himself entangled in a series of lawsuits brought by the displaced tenants. Finding the pace of French law intolerable and the lawyers corrupt, he decided to conclude the matter with a goldsmith’s directness.

After receiving news of an unjust court decision in Paris, he took to the streets with a “great dagger”. He first tracked down the primary plaintiff: “I wounded him in the legs and arms so severely, taking care, however, not to kill him, that I deprived him of the use of both his legs.” Not content with this, he grabbed a second man involved in the suit and treated him with similar violence until the legal action was dropped.

The Saliera: A Trophy of Power

It was in this atmosphere of constant threat and frantic creation that he completed the Saliera (1543). Made in gold and decorated with exquisite enamel, it was a staggering display of technical virtuosity. The intertwined figures of Neptune (God of the Sea) and Tellus (Goddess of the Earth) represented the union of the two elements. The piece condensed everything Francis I admired in the Italian Renaissance: beauty, violence, and sensuality, all channelled through the artist’s terribilità.

As the only major work of goldsmithing to survive from Cellini’s hand, it stands as a peak of Renaissance luxury. To the King, the Saliera and Cellini’s service was not just about table ornaments and beaty, but about demonstrating his power.

The legendary status of the Saliera was cemented in May 2003 when it was stolen from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The thief, Robert Mang, was a security expert who realised the museum’s alarms were outdated. He climbed a scaffolding, smashed a window, and took the piece. For three years, the art world feared the “Mona Lisa of Sculpture” would be melted down for its gold.

The recovery was as strange as any of Cellini’s stories. Mang buried the sculpture in a lead box in an Austrian forest. He eventually sent the gold trident from Neptune’s hand to the authorities as a “proof of life” for the statue. Following a sting operation involving a mobile phone used for ransom negotiations, Mang surrendered, and the piece was recovered from the dirt in 2006. Its value was estimated at roughly $60 million, but its historical significance remains essentially priceless.

Casting the Perseus (1549)

Cellini’s return to Florence in 1545 was not a homecoming of peace, but a final attempt to secure his legacy among the giants of the Renaissance. Under the patronage of Cosimo I de’ Medici, he was commissioned to create a bronze statue of Perseus with the Head of Medusa for the Loggia dei Lanzi. This was a challenge to his very identity; he had to prove that the “goldsmith” could handle the violent, large-scale alchemy of monumental bronze casting.

Upon his return, the casting of the Perseus became a physical battle against the elements. The climax of this project remains one of the most famous episodes in the history of art. As the metal was being heated in the furnace, a massive storm broke out, flooding the workshop and cooling the fire. Cellini, already suffering from a debilitating fever, dragged himself from his bed to find his assistants in despair. The bronze had “curdled”—it was becoming too thick to flow into the intricate mold.

In a frenzy of improvisation, Cellini ordered more wood for the furnace and, realizing the alloy was still too viscous, commanded his servants to bring him every piece of pewter tableware from his house. He threw nearly two hundred platters and bowls into the molten mass. The tin in the pewter lowered the melting point of the bronze, allowing the liquid metal to finally surge into the mold. The resulting statue was a technical miracle, cast in a single piece from the neck down, a defiant testament to a man who refused to be defeated by the elements, his body, or the law.

The Final Days of the Renaissance Man

Cellini lived another two decades after the Perseus, eventually turning his focus toward his autobiography, La Vita. It was in these pages that he codified his own myth, ensuring that his perspective would survive long after his patrons and enemies were gone.

He died in 1571, having transitioned from the street-fighting goldsmith of Rome to a foundational figure of the Mannerist movement. He left behind a legacy that is impossible to separate: the sublime beauty of the Saliera and the Perseus forever entwined with the cold-blooded efficiency of the pugnale.

The Toxic Alchemy of a Renaissance Workshop

Behind the bloody narratives of La Vita may lie a physiological reality often overlooked, which we covered in the article on Caravaggio. In the Renaissance, goldsmithing was a trade of high toxicity. To gild his masterpieces, Cellini utilised fire-gilding, a process where gold is amalgamated with mercury and then heated, releasing lethal fumes. Without modern ventilation, he spent decades inhaling a cocktail of mercury, lead, and antimony.

The clinical symptoms of such chronic poisoning align with several of the more volatile aspects of Cellini’s life. Heavy metal toxicity is known to cause extreme irritability and sudden, explosive “mad bull” outbursts. It also manifests as deep-seated paranoia—a condition that echoes through Cellini’s constant suspicion that his rivals were seasoning his food with ‘crushed diamonds’ or conspiring in every shadow. Furthermore, chronic exposure is linked to physical tremors, intense fevers, and cognitive disturbances, all of which Cellini documented throughout his career, most notably during the frantic casting of the Perseus. While he attributed his survival to divine favour and his ailments to the malice of others, the medical reality of his craft could suggest that the very tools he used to create beauty were simultaneously eroding his health and temperament.