I was recently contacted by American National Public Radio to comment on the incident where Olga Kharlan declined to shake hands with her Russian counterpart, Anna Smirnova, after their match in the World Championships in Milan. The article on NPR was very limited, and almost none of the information I provided was included, so I thought it might be a good opportunity to dig a little deeper into the history of handshakes in fencing. How far back do they actually go? And do they matter?

While the refusal to engage in this customary post-match handshake may appear trivial to many, it is historically a significant issue. If anyone missed what happened, Kharlan was initially disqualified for refusing the handshake. The decision was ultimately reversed, but the whole matter ignited fervent discussions and raised questions about the role of the handshake in the context of modern fencing. MMA fighters often refuse to touch gloves after all, so what’s the big deal?

Let me first be clear that I am not specifically commenting on Kharlan’s refusal here. I think we can all understand why she acted the way she did due to the war in Ukraine. I am just providing some historical context for the salute and handshake as an integrated part of fencing culture.

The first record of the handshake

To get some help in digging up the history of the handshake in fencing, I spoke to the Godfather of HEMA, Matt Galas. According to him, one of the earliest fencing competitions that we have on record took place in Normandy, sometime around 1420. During one of the bouts, a terrible accident occurred. One of the fencers charged in and was accidentally killed by an unfortunate blow that entered his eye.

”At the time, this type of incident was automatically seen as a murder until proven otherwise. So, to avoid revenge by relatives, it was customary for a killer to leave the area and seek legal counsel elsewhere,” Galas says.

That is exactly what happened on this occasion too. The fencer who had dealt the lethal blow fled the scene and wrote a letter of remission to the authorities from his exile.

”It is this letter of remission which provides us with the first recorded instance of a fencing competition of this type. That’s interesting on its own, of course, but in this letter, the killer uses a peculiar argument in his defense. He states that he did not mean to kill the opponent, and as proof of his good intentions, he claims that they had shaken hands before the bout ’as is customary among fencers’,” Galas explains.

A longstanding and widespread tradition

So, not only does the handshake date back a long time, but it has also been widespread and consistently upheld through the ages in relation to fencing culture. The usual penalty for refusal was, however, not disqualification but a fine. Not surprising at all for anyone who is familiar with historical fencing guild rules, since fines seemed to have been an important way of keeping fencers from behaving poorly in general, be it to keep them from making lewd comments about women or spitting.

Galas also mentions the rules from a Dutch fencing guild in Bergen Op Zoom. “The guild rules from 1480 state that after a bout, the fencers lay down their weapons and shake hands”, he says.

“Item: whenever someone has laid down his sword and does not shake hands with his master and his opponent, he shall be fined one Flemish Groat.“

Dutch fencing guild laws from Bergen Op Zoom

”If a scholar or guild brother comes in and doesn’t greet everyone, fined a half Groat.”

Yet another example comes from the Chatelet ordinance from Paris in 1520, which dictates that fencers must “Touche en la main,” or shake hands. He who does not shake hands with his opponent and the master after putting weapons down on the ground will pay a fine.

In the “Ensayo de un tratado de esgrima de florete” by Gregorio María Dueñas (Toledo, 1881), we can read the following: “When terminating all assaults, after removing the gloves, the contestants should cordially extend their hands toward one another, out of courtesy and as a sign of no resentment.”

The difference between Play and Earnest fencing

In historical records, a noticeable distinction can be noted between earnest fighting and playful bouts. Whenever two individuals engage in a playfight (sparring), there’s always a risk that emotions may escalate, potentially leading to a genuine conflict, particularly if the fencers approach it differently. Therefore, certain techniques and target areas are often excluded in a playfight. Consequently, friendly matches also require a set ritual and format, signifying a mutual understanding where both fencers agree not to inflict intentional harm. The regulations and etiquette surrounding the handshake serve to underscore the amicable nature of these bouts, distinguishing them from real conflicts. The pre-match handshake signifies goodwill and clear intentions, while the post-match handshake signals the end of the match without lingering animosity.

“And if you do this as you approach him, then you are doing in play what is good in earnest. And always seek the upper opening rather than the lower and go in over the cross guard.”

MS 3227a

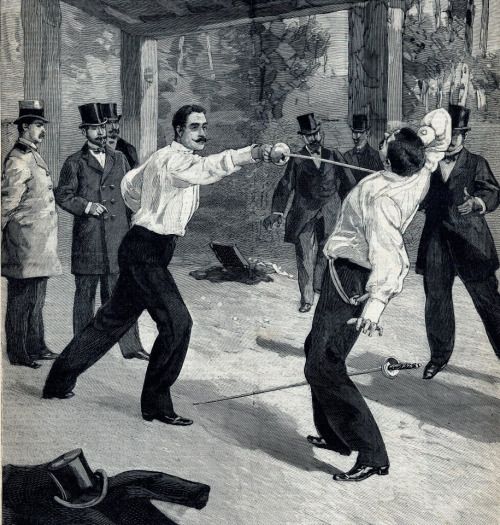

The Duel – Let’s shake on It

Historical fencers often view sport fencing as something entirely modern and separated from historical roots, but sport fencing can trace its lineage to the historical fencing art and particularly to the fencing culture associated with their weapons. During the 17th century through 19th century, fencing arts were closely affiliated with duelling and the culture surrounding its practice. Although sport fencing has become a modern sport, ithas kept a lot of the attitudes and traditions of honourable conduct associated with this practice (although there are certainly some behaviors that would have been scorned historically among modern fencers), and the handshake is one such tradition.

When it comes to the duel, it could be said that it is a phenomenon somewhere in between brutish real violence and a bout in the fencing hall. It certainly includes a real conflict and intentions to harm the opponent, but it isn’t frivolous mayhem. It has stringent rules an is expected to be an honourable affair. The duel serves as a formalized means of resolving disputes where honour has been tarnished. Unsurprisingly, participants were therefore obliged to conduct themselves honourably throughout the duel. Breaking the rules of the duel would defeat the very purpose of having a duel in the first place. It could be said that paying homage to the culture and formalities of the duel, was actually part of the duel itself – and that included a handshake.

In the duel, the handshake symbolized that the matter had been settled, honour had been restored, and hostilities had ended. I am certain this wasn’t always the case, and that grievances were upheld indefinitely, regardless if the duel was over. But equally, an adherence to decorum could sometimes take extreme forms, where duellists went above and beyond in following the format.

One such instance was the duel between the Jewish officer Captain Armand Mayer and Marquis Amédée de Morès duel, over an article accusing Jewish officers of treason – a duel which we’ve written about before here on The Historical Fencer. The duel was over in seconds as Morès’ saber penetrated Mayer’s lung and was stopped only by his spine. And even though Mayer must have known he was likely mortally wounded by a man accusing him of treason, and even though Morès detested Jews, the two men shook hands. Afterwards, Mayer was taken to a hospital where he died later that afternoon.

The modern left-handed handshake

As a little side-note, there’s a peculiarity about the modern sport fencing handshake, where fencers shake with their off-hand. It is said that this comes from the fact that you are not supposed to wear a glove on the hand when you shake hands, and since sport fencers only wear a glove on their weapon hand, they shake with the other. If that’s the case, it is an odd tradition, since the original meaning of a handshake is to show that you don’t hold a weapon at all. That is possibly the reason why some of the earlier fencing rules said to put down the weapons and then shake hands.

An alternative explanation for shaking with the off hand, is that it is a practicality due to the electronic attachment on the weapon hand. This would make it a much more recent custom and a much more likely explanation given the direction in classical fencing to remove the gloves before shaking hands (as seen in the regulations from Toledo mentioned earlier).

A final handshake on the handshake

In our modern world, Kharlan’s refusal to shake hands may seem like a minor breech of decorum. Yet, when viewed through the lens of history, it carries weight. A seemingly simple gesture holds centuries of tradition and the values of honour and decorum in the world of fencing. In her position, it can certainly be argued as defensible, and historically a disqualification can be seen as a harsher punishment than a fine. But as principle, the handshake is a nice custom with a long history, that I hope will be upheld.

Acknowledgments:

A big thank you to the Godfather of HEMA, Matt Galas.

Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez, for the translation of Ensayo de un tratado de esgrima de florete. Toledo, 1881