On this day, December 29th in 1386, two knights fought to the death in a judicial duel behind a monastery in Paris. They were surrounded by thousands of onlookers, watching as one man straddled the other, demanding a confession of a most horrible crime. Only one of them could survive in one of the last judicial duels in France.

Squire Jacques le Gris and Sir Jean de Carrouge were once close friends. Le Gris had even been the Godfather of Carrouge’s first son, something that was considered a great honour at the time and almost made them as close as family. They had both served Count Robert of Perche before his untimely death and they then both swore allegiance to their new lord, Count Pierre d’Alençon. This marked the beginning of a great career for Le Gris, who quickly became the new lord’s favourite, and the beginning of a long descent for Carrouge.

Jacques Le Gris in particular was high in the Count’s favour. He was especially fond of him and placed great trust in him.

Froissart on the Count’s favourite

Le Gris came from humble beginnings, his family far from as prestigious as the Carrouge lineage. But although Jacques’s family may have been humble, the young squire excelled and was educated and amiable, possibly also a lady’s man, much like the count who openly had mistresses at the court. On top of this, he was known to be exceptionally strong. Good looks, strength, brains and the count’s favourite… For Jacques, things were looking up. Maybe it was with some jealousy then that Jean de Carrouge saw himself left behind in the new court to which they now belonged.

Jean de Carrouge was also ambitious. As the main heir of his family, he knew it was up to him to secure the name of his family in the annals of history. His only brother was a priest and therefore would leave no heirs. Jean tried hard to make choices that would further his family’s estate and glory, but for a very long time, he didn’t seem have much luck. And it all started when both his wife and son died. Lady Fortuna only seemed to have eyes for one of the two friends.

Going to war and finding a new wife

In one blow, Jean was left alone, without a family, and with no heir. Perhaps struck by grief, he joined the famous admiral of France, Jean de Vienne, to fight the English. At this time, in 1379, King Charles V wanted to rid Normandy of the English, and Jean was one of many knights who answered the call to fight. There are several records of him in locations across the Cotentin Peninsula during the many months he participated in the campaign.

Perhaps it was also then he set his eyes on a new wife. Three years after he had returned home, he remarried. This time to a wealthy, modest and beautiful woman called Marguerite de Thibouville, whose family name had been tainted by two accounts of treason by her father towards the King. Both times he, with the grace of God, escaped with his head still attached to his body.

Jealousy and conflict with his old friend

The marriage did however not just bring wealth and good fortune. Maybe it was due to his ambitions, or a sense of pride and entitlement, but Carrouge started a dispute with both his Lord, Count Pierre, as well as his old friend, Jacques Le Gris. Jacques had received a piece of land from the Count, which brought him considerable wealth. This land had been purchased from Jean’s father-in-law. Seeing himself being passed by a man from a lesser family, Jean started a legal process to retain the land which he felt was unjustly given to someone else but him. The quarrel went as high as the King, who also was a cousin to the Count. The King supported his cousin in the affair, and that meant that Le Gris had the right to the land, much to the dismay of Carrouge.

Left in the cold

This marked a steep decline in his career, while at the same time Le Gris continued his advancement and gained access to the highest nobility of the country. He was even appointed the honorary title of Royal squire. Carrouge however, was out in the cold. In 1382, Jean’s father died and he was expected to inherit his title as Captain of Bellême, but the Count gave the title to another man. This was a very public humiliation and most likely due to the trouble Carrouge had caused him earlier. Jean would not stand for it, he had now sunk below the rank of Jacques in the court, so he made the foolish decision to sue his own Count for the title. Of course, he lost.

But the real insult came the following year, in 1383, when Jean decided to purchase some land areas. Only twelve days after the purchase, the Count demanded he give them up due to a prior claim. Once again, Jean lost the fight, and had to sell the lands to his lord.

It’s not surprising then, that Jean withdrew from court, isolating himself with his new wife.

Making peace with his old friend

For over a year, Jean and Jacques remained enemies, until Jean Crespin – a mutual friend of the two men – invited them both to a celebration of his newborn son. They met in Crespin’s great hall with everyone watching them in suspense. Jean walked up to Jacques with an outstretched hand, and to the sheer of all assembled, they shook hands. Jean then told his wife, Marguerite, to kiss Jacques, as a sign that their quarrels were now at an end, which she did. During the night, the old friends drank together, and all troubles seemed to be over.

A disastrous campaign

In May 1385, Jean once again joined the Admiral of France to engage the English, who had been plundering and ravaging the French countryside. This time they set of from Sluys and travelled up to Scotland where they would merge with Scottish forces. The campaign was absolutely brutal. The Scottish turned out to be far from dedicated to the venture and they would abandon the French, and the Scottish king even demanded a bribe to participate. The French then went about to slaughter and pillage English villages and castles for six months, slipping out of a direct confrontation with the English king Richard II after the Scots had withdrawn. The English King had his revenge on Edinburgh instead, which he found abandoned, and he burnt it to the ground.

The French who had circled the English army unsuccessfully attacked Carlisle. As they then retreated North again, with their significant loot, they were attacked from behind by Sir Henry Percy, the son of the Earl of Northumberland. The Englishman managed to kill many of the French and took 26 of the Nobles as prisoners. Jean de Carrouge was, luckily, not one of them. He managed to get back to Scotland, together with the remnants of the French forces. What had started out as a gallant and impressive army was now in tatters, most of the riches gone. Jean returned to France poorer than he had set out, and also in poor health. But there was one thing that he had gained, which may have made the campaign worth all the sacrifice, he had been knighted.

The crime of Jacques Le Gris

Not much had gone the way that Jean hoped in his life. He was now fifty years old and many of his enterprises had led to nothing. But there was one good thing, his wife. Although she still hadn’t given him any children, they spoke fondly of each other and he had nothing but praise for her. The campaign in Scotland was the first time they were away from each other for a longer period of time, but almost immediately after his return, Jean decided to go to Paris on a business trip. On the way he stopped by the court of the Count Pierre d’Alençon, where he ran into Jacques Le Gris. What passed between the men is unclear. Maybe it was Jacques’s turn to be jealous of the Knighthood bestowed upon Jean, maybe Jean insulted him in some way, or maybe he laid eyes on the young and exceptionally beautiful Marguerite and decided he wanted his old friend’s wife too. In the meeting, he did learn that Jean was travelling to Paris, and that Marguerite was staying with her mother-in-law. Through a loyal friend, called Louvel, he soon learned that Marguerite was left to her own devices in the small chateaux, and decided to act.

Lady, I swear to you that I love you better than my life, but I must have my will of you.

Jacques Le Gris to Marguerite, according to Froissart

Marguerite was taken by surprise when Louvel and Jacques showed up at the house. He first tried to get inside through a story of an unpaid debt, before he confessed his love for her. When she made it clear she wasn’t interested, he grabbed her by the wrist and forced his way inside the house. He then said he would pay for having sex with her, which she promptly refused. When nothing he said worked on the loyal wife, him and Louvel grabbed her and forced her to the bedroom. Marguerite was not a woman who would easily just take abuse, and she tried to fight both men, so in the end they tied her down and gagged her. As the Lady was nearly suffocating from the struggle and the restrictions, Jacques had his way with her. When he was done, he again offered her money for her silence. “I don’t want your money. I want justice!” she replied. Le Gris made it clear to her, that she had nothing to gain from accusing her. He had made sure he had an alibi and that he had covered his tracks.

Legal proceedings

When Jean returned from his business trip he found his wife in a saddened state and not her usual happy self. She refused to tell him what had happened before they were alone and going to bed. In tears, she revealed the story.

There must have been doubt in Marguerite’s mind whether her husband would believe her, but Jean took his wife’s side. He demanded justice and took the accusations to the only place he could, the Count. It must have been fairly clear to him that he stood little chance to win the case after so much history and animosity, not just between Jean and Jacques, but also between Jean and the Count himself. Sure enough, not only did the Count dismiss the case, stating that Jacques was completely innocent, he also said that Marguerite must have “dreamt it”.

According to the law, Jean could appeal to a higher authority. In this case, that was the King himself. He travelled to Paris. The first thing he did, was to seek legal counsel, before presenting himself to the King. When doing so, it was with an unusual plea. He didn’t ask the king to overrule the Count’s verdict through normal means, instead he invoked the ancient right of a judicial duel.

Judicial duels – With God as judge

A judicial duel is a different entity from an honour duel. It was actually a part of the legal system, and the idea was that in cases where a decision couldn’t be made on guilt, God would instead decide the verdict. The practice of judicial duelling is older than Christianity however, and it was introduced in Normandy by the Vikings, from whom several descriptions remain. By the 14thcentury, however, it was rare that this legal action was taken, and both Kings and the Church disliked the practice. Previously, it had not been unknown that the Church engaged in judicial duels, as we have written about here.

The legal proceedings took time and were costly. For Jean, everything was at stake: his honour, his finances, his land and his life. For Marguerite the same was true. If it came to a judicial duel, she would not escape the verdict; if her husband lost, she would be burnt alive. What was even more troubling perhaps, was that she was with child. It must have been quite unclear for her who the father was, and what would become of the child if both parents were killed and their estates seized?

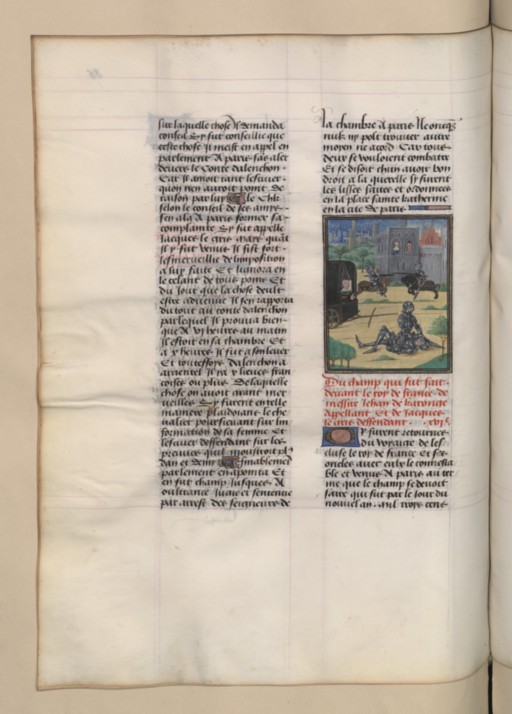

In September, the Parlement delivered its decision. Jean’s request for a judicial duel was granted since the court had investigated the matter thoroughly and couldn’t decide on the issue of guilt. It was the first duel for a rape charge in over 30 years in France. Perhaps one of the reasons to accept the duel was that one of Jacques’s alibis had been arrested for raping a woman while in Paris during the trial.

Preparations to die or kill for holy justice

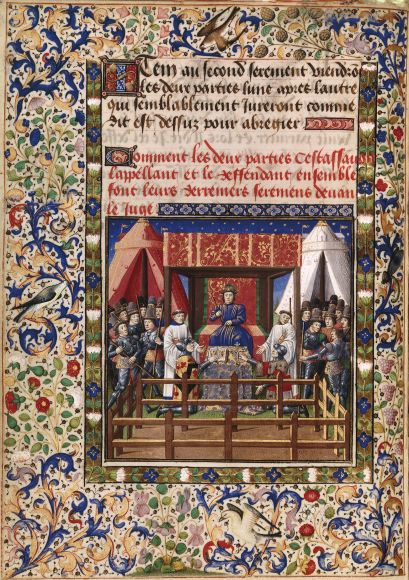

The duel was to be fought outside the monastery Saint-Martin-des-Champs, where new lists were raised for the two men and all the spectators. The field was surrounded by a tall inner wooden wall and a lower outer wall. The inner wall was so tall and sturdy that no one could escape, and no one could get in. On each side of the compound there were gates, where the opponents would enter. A third gate was used by the officials, and at each corner was a tower from where they could overlook the fight. On either side of the field, platforms were raised where the combatants could wait, swear their oaths and where their tents were raised. The entire arena was then provided with fresh sand, which was raked to provide a smooth and even surface.

The duel was first supposed to be fought on November 24, but the King requested it to be postponed so that he could watch, so a new date was set: December 29. The King wasn’t the only one who looked forward to see the duel. On the day, thousands of people from all social classes gathered to watch the last duel to be approved by the Parlement of Paris.

The fighters heard mass, prayed and ate before being dressed in armour. In procession, they then rode through the streets to the lists where they would fight. The sources note that Marguerite was all dressed in black mourning attire, surrounded by her father and relatives.

As they arrived at the field, both the squire and the Knight stated their business and their claims. They were then let into the arena, and Marguerite was placed on a scaffold overlooking the arena.

The rituals surrounding the duel were extensive. Rules were read publicly, oaths were sworn and everything was done to ensure the fight was just and fair in every possible way. That included knighting Jacques le Gris, so that both men were of the same social standing. Afterwards, they both knelt by a table and clasped hands, laying forward their righteous claims and swearing another oath. They then kissed the crucifix.

After all the ceremonies, Jean walked up to his wife and said: “Lady, on your evidence I am about to hazard my life in combat with Jacques Le Gris. You know whether my cause is just and true.” To which Marguerite replied: “My Lord, it is so, and you can fight with confidence, for the cause is just.” Jean then kissed his wife, clasped her hand and made the sign of the cross.

The duel only one can survive

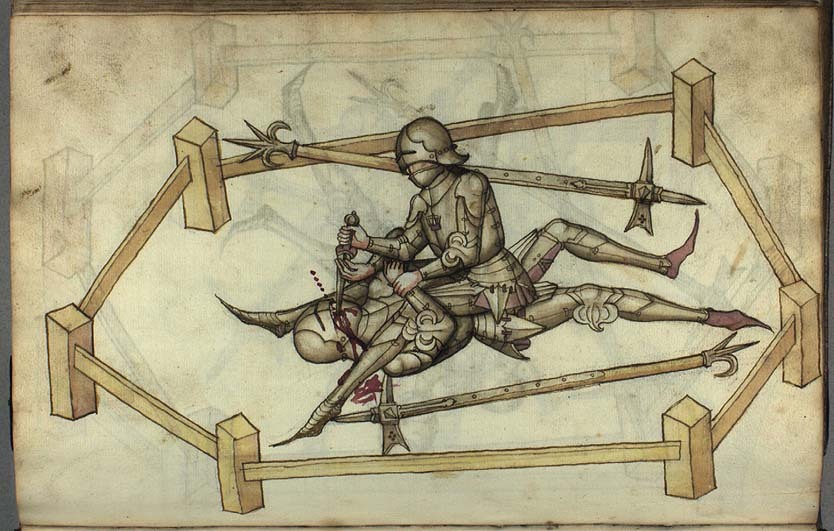

According to the famous chronicler Froissart, the two men started the engagement on horseback, but failed to do any damage. They then abandoned their horses and continued on foot with swords. From what we know of fencing in armour at the time, both men would have been using half-swording techniques and wrestling. That means that they held the swords with one hand on the blade and the other on the grip, using them as spears.

As the men fought, Le Gris managed to thrust the tip of his sword into the thigh of Jean, drawing blood. There are no known details of exactly where he managed to injure his opponent, except that it was too superficial to do any real damage. Froissart says he should have pushed it in farther, which probably means he managed to reach an opening, but failed to press the sword into the gap far enough. Given the construction of armour at the time, it was probably a wound high on the inside of the thigh or to the backside of the thigh. Jean then called out: “Our quarrel is judged this day!” after which he closed to wrestle, grabbing Jacques at the top of his helmet, and throwing him to the ground. He then took his sword and descended on his opponent, demanding he confess his crime. Jacques Le Gris, however, did nothing of the sort. The men struggled on the ground until Jean managed to push his sword into a gap in the armour, killing the man who was once his closest friend.

After thanking the King and the great nobles, the knight went to his wife and kissed her, then they went together to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame to make their thank-offerings before returning to their house.

Account after Froissart

The aftermath of the duel and the death of a Knight

After the duel, Jacques’s body was dragged through the streets to a cemetery for criminals, whereas Jean now was a famous man. He received money and honour from the Parlement of Paris, and then became Royal Chamberlain and in 1390 he was awarded both riches as well as a title of Chevaliers d’honoeur.

His new-found respect and position at the royal court, made him one of the country’s most well-known and important knights. He was often called upon to take on various tasks as part of the King’s retinue. In 1396, a most pressing matter took precedence over everything else. Since Muhammed’s time, the Islamic world had been encroaching Christianity and by the 14thcentury it was a fight that had been ongoing for 700 years and it was once again getting closer to home.

In the 7thcentury, the Arabs had colonized much of the Middle East, and greatly reduced the Byzantine Empire, whereas many other civilisations were completely destroyed. The expansion reached as far as France before being pushed back at Tours in 732 and it would take until 1492 before all of Spain was freed. So the threat was very real for the Christian world. The Islamic expansion had also been a complete catastrophe for the people in the areas, who lived under oppression. Only 10% of the populations in Iran, Iraq, North Africa and Spain were Muslims in the 8thcentury, it was only in the Arabian Peninsula that the Muslims constituted a greater portion than this, but over time, Arab tribes would move in and Christians became fewer and fewer, suffering high taxation that was used to fund islamic military campaigns, and often making Christians so poor they had to sell their children into slavery. Therefore, many Christians converted, but Syria for example was likely still a Christian majority country during the Mongol invasion of the 13thcentury. In 1299, a new Islamic empire had seen the light of day, and by 1390, the Ottoman imperialist ambitions threatened the South East of Christendom, and they couldn’t be ignored.

The previous leader of the Ottomans, Orhan, had sworn to invade Europe and had gained a foothold in Gallipoli from which he terrorized the Greeks, Bulgarians and Byzantines. His successor, Murad I, had taken the Byzantine city of Adrianople in 1362, renamed it Erdine and made it his capital. This was moving the front farther into Christian territory and by the 1370s he had taken all of Thrace, and began conquering the Balkans, forcing Bulgarian and Serbian rulers into vassalage. In 1392, the last Serbian prince fell. In 1393 the Bulgarian tsar Ivan Shishman had lost the capital, Nicopolis, to the Ottomans, and his brother had been forced to become an Ottoman vassal. Hungary was now the last line of defence for the Christians, so, in 1396 France joined one of the last big crusades against the Turks together with Hungary. They tried besieging Nicopolis in September of that year, and Jean de Carrouge was part of the 5,000 French knights on that field. The proud French nobility caused their own doom however, when they refused to follow the orders of the Hungarian king Sigismund, as the city was relieved by Turkish forces. To the great dismay of Admiral Vienne, under whom Carrouge once again was fighting, the Count of Eu lead an attack which would prove disastrous. Both Carrouge, as well as the Admiral of France, fell during the battle. After the battle there was a massacre of the Christians knights and soldiers, as revenge for the killing of muslim prisoners at Rachowa.

Sources:

The duel between Jean Carrouge and Jacques Le Gris is well documented. There are many primary sources, both chronicles as well as documentation like interrogation protocols. Froissart is perhaps the most well-known. A well-researched and pleasurable read on the topic is The Last Duel, by Eric Jager. It does however contain some mistakes and exaggerations that go beyond what the sources tell us. He extrapolates information on the actual fighting from other duels and he also misses that a “hache” in the historical sense, is usually translated as a poleaxe, as seen in the French fight book Jeu de la hache (written around 1400) (although in Froissart, there is a depiction of axes that aren’t the typical poleaxes). Still, The Last Duel, provides a nice read for the historically interested and has a lot of fantastic detail, from which I have drawn information I previously didn’t have access to.