The last German student to die as a result of a duel using thrusting swords—not unlike the French épée de combat—was the young jurist Adolph Erdmannsdörffer. Buried in the village cemetery at Wöllnitz, now integrated into the Thuringian town of Jena, his grave marker recalls him as “das letzte Opfer der Stoßmensur” (the last victim of the thrust Mensur).

The worst part: It was his own fault.

It’s a typical village church surrounded by a typical village cemetery: Quiet, well-kept and contained. Its only claim to fame is a single grave marked by a porcelain plaque. Tightly choked by English ivy, this is the last resting place of Adolph Erdmanndörffer.

If that name doesn’t ring a bell, consider this: In a way, this is also the grave of a bloody, 200-year custom practiced in the nearby University town of Jena, and a handful of other university towns scattered around Germany, that cost dozens of young men their lives: Erdmannsdörffer’s death was the final nail in the coffin of the akademisches Stoßduell, the duel with thrusting swords among university students.

Origin Story

Scraps, fights, and duels with thrusting swords had been a constant phenomenon in 17th- and 18th-century German university life. The number of incidents waxed and waned over the decades, depending on the political situation, the ups and downs of economic cycles, on wars and plagues, and especially on the moral and religious climate of the times.

During some periods, several students died at each others’ hands within a few years. At other times, decades could pass between killings.

Most of these encounters resulted from mixing three combustible elements: Testosterone, steel, and alcohol. No matter the outcome, the consequences could be devastating to the participants: Death, mutilation and lasting illness, or, at best, relegation from the university. Those who by skill or, more frequently, chance, managed to outlast their opponents, faced murder charges and the hangman.

If they had removed themselves from the jurisdiction, the university and local authorities would actually make the effort to hang the surviving duelist in effigy.

In Germany, the sword as sidearm had always played a pre-eminent role as a badge of rank and standing. Originally a privilege of the nobility, carrying the Degen on your side was a visible sign of belonging to the top tier of society. Even university professors didn’t want to stand back to the Degen of their aristocratic students and demanded a sword to go with their robes and vestments of office. The young aristocrats’ bürgerlich fellow students didn’t either—and neither did the craftsmen’s apprentices who rubbed elbows and scrapped with the students.

In the last decades of the 18th century, everyone was wearing a sword on his side in university towns like Jena, Halle, Erlangen, or Würzburg.

Überfall, Ataque, Rencontre, Duel & Tumultus

Faselius (1805), at 33f, created a “Register of all Persons who, between 1531 and 1804, lost their lives by unnatural death”. (1) Listing the names of the victims (and, where available, perpetrators) and manner of death, this compilation provides us with a rough grid of the kind of confrontations that could cost a student his life:

Like today in bad parts of town all over the world, an Überfall — an unexpected attack by one or several opponents — could happen anywhere and at anytime, especially while traveling. One area near Jena was especially notorious — the Mühltal, a barren, desolate valley whose ill-reputed inns “Die böse Grind” (Evil Scab) and “Die Filzlaus” (literally, “the crab”—not in the marine biology meaning) were so rough they were razed by the government in 1732.

There could be one or several opponents belonging to different social classes: Here is a selection from Faselius:

- 1585. On Dec. 28. Dec., a Studiosus from Denmark was beaten to death by the peasants in Burgau;

- 1608. On Apr.18, noble Studiosus was pelted to death with stones on the Steinweg;

- 1614. Aug. 16, Studiosus Gauer, from Styria, was murdered and beaten to death at 10:00 PM;

- 1669. Nov. 26, the coachman Teschner was killed at night by students Matthiae from Oschersleben and Oldvock from Kiel;

- 1689. Apr. 28, Studiosus Weitz from Gotha, died as a result as something being thrown at him;

- 1706. May 26, at Lobeda, 2 Luca students, Krüger from Spremberg, and Karsten, from Holstein, were murderously beaten to death by the citizens and peasants.

- 1725. Sept. 30,Herr Köster, Studiosus of theology from the Palatinate, was beaten to death with a tree by the tanner Gräfe near Kreußlers house in Oberlauengasse. (Yes, that’s the residence of the famous Kreußler fencing master dynasty).

The At(t)aque differs from the Überfall only in that the victim is given a chance to defend himself — in the case draw his sword. There was no emphasis on fair play, especially when combatants belonging to different social classes were involved. Here are a few cases from Faselius’ death roll:

- 1561, August 3, Herr Christian von Podewills, student from Pomerania, was stabbed to death (erstochen) at 10PM;

- 1581, Febr. 5, Studiosus Herr von Silbitz, was stabbed to death..

- 1605. Aug. 29 carpenter Steckenberger was stabbed to death by a student;

- 1606. Apr. 10, Johann Stötzer, Studiosus of Theology was Stabes to death by the goldsmith Schmid;

- 1609. January 9, Studiosus Bartsch from Eblingen, was stabbed to death.

- 1609. Nov. 28, Studiosus Sebisch, from Breslau, was stabbed to death and murdered behind the cit council building;

- 1614. Jan. 23, Studiosus Nandelsted from Altenburg, stabbed to death.

- 1619. Jun. 21, Georg Reichenbach, a teaching assistant, was cut to death by a student;

- 1627. Jun. 5, Studiosus of Laws Graf, from Leutershausen, was killed by a nobleman student;.

- 1634. Dec. 20, Christian Liebold was stabbed to death by a student;

- 1637. Febr. 20 Studiosus Klepper was stabbed to death;.

- 1637. May 7, Student Gerold was stabbed to death by a butcher;

- 1686 am May 3, hatmaker journeyman Haupt from Fürstenwalde was so severely wounded by students that he died immediately;

- 1691. Jan. 7, Friedrich Christoph Ziegenhorn, a goldsmith’s apprentice, was killed by a student;

- 1721. Nov. 3, local barrelmaker Mstr. Scharre, was stabbed to death by a Studioso on the Camsdorfer bridge;

- 1763 Sept. 8 local butcher Mstr. Seyfarth was stabbed to death at 11PM by Studiosus of Theology, Mitlacher, at the Gasthof zum Engel.

An Ataque could seamlessly blossom into a Rencontre, a combat to the death without rules or regulations, usually in the dark, in a back alley, or in front of the tavern where it had originated.

Whenever members of student’s societies rubbed against each other — young men of equal status and subject to the internal regulations of these organizations and the customs of inter-organizational business — a Duel lay in the air.

Faselius sets these deaths apart from common death in the streets by the descriptor “im Duell erstochen” — stabbed to death in a duel.

Until the very early 1800’s, duels required an escalation of insults:

The worst verbal insult was the dumme Junge (“stupid boy”), which could not be überstürzt (“toppled”) by another invective. To set himself in “Avantage” (the challenged party had the choice of location and the first thrust), the titular dumme Junge had to strike the insulting party in the face. This in turn was “toppled” by application of the riding crop to the physiology of the dumme Junge. If the conflict happened to occur inside the chambers of a student, the remaining option to “topple” was the emptying of the chamber pot with the night soil over the head of the challenger.

If the conflict arose outside, the dumme Junge was literally shit out of luck and had to issue the challenge, losing Avantage.

The initial insult could be quite unimportant: blowing out a candle when asked not to do so would do. Or making negative comments on a fellow’s colored cap — usually reflecting the color of the student society he belonged to.

And it is here that we catch back up with Adolph Erdmannsdörffer.

Last Blood

He was born in Altenburg (Thuringia) and attended the famous university at Jena, where he enrolled to read law and became a member of the student fraternity Burschenschaft auf dem Fürstenkeller, a forerunner of today’s Germania Jena.

A brief note in a German newspaper[2] provides a condensed account of what happened.

On July 24, 1845, Studiosus Erdmannsdörffer initiated a verbal altercation with a young physician, Gustav Köhler from Eisenach. The reason: The color of Köhler’s fraternity cap. (He was a member of the Burgkelleraner, a rival Burschenschaft).

Köhler, who had already graduated and was about to get married, tried not to get drawn into a full-blown confrontation. Technically, he had enjoyed immunity from being called to fight since his last year of studies. But despite the mediating measures of the Court of Honor, despite his seniority, the affair ended in a challenge to fight with “Pariser Degen”.

Pariser is not Pariser

A few words about the “Pariser” are in order:

Today’s mostly amateur historians of student life use the term “Pariser” as synonymous for any thrusting weapon used in an academic Stoßduell.

This is not quite accurate. The duels among students in the 17th and 18th century were the individual sidearms carried by a student. They were smallswords and reflected the contemporary (and mostly French) fashions of the day. The Germans used the word Parisien to describe this weapon, which found good use in rencontres and duels.

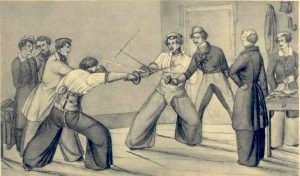

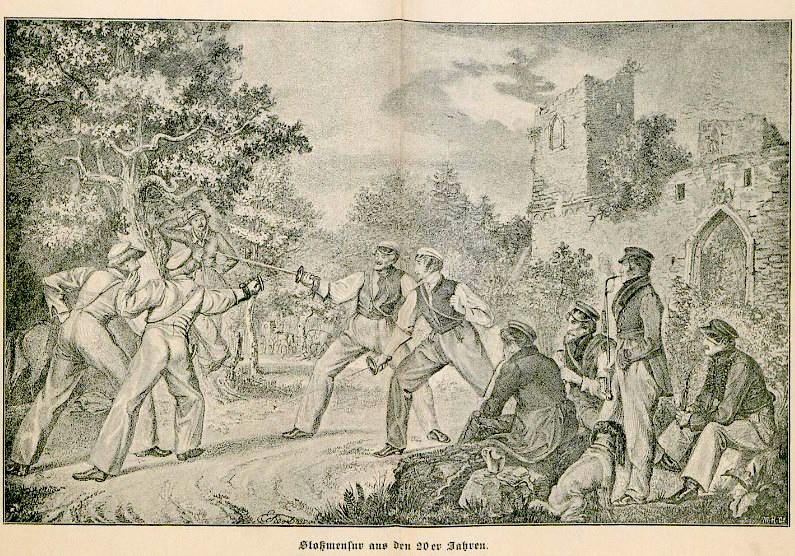

However, the weapons used for the Stoßduell of the student societies was the Jenaer Stoßschläger — with its triangular Schilfklinge and very large, targe-sized circular guard, its threaded tang and screw-on pommel, which made it ideal for concealed carrying of the weapon’s parts.

The Stoßschläger served for the basic level of the duel. If a more severe level was called for, the seconds attached to each fencer were moved and the duelists employed “Pariser Degen”. These corresponded by and large to the French dueling épées of the early 19th century: A foil hilt equipped with a triangular épée blade. The smaller hilt provided far less protection than the Stoßschläger hilt.

By 1845, seven years after a local law that prohibited the possession of épée blades and placed substantial fines on cutlers and metal workers for selling or even repairing thrusting weapons, the inventory of weapons available to aspiring duelists probably consisted of improvised weapons… shallow cup hilts, perhaps improvised leather hilts… all of which were encompassed under “Pariser Degen”…

A Night to Remember

On the evening of July 25th, the duelists meet at a neighboring village. It is unclear if the duel was for the usual 24 Gänge (a Gang being ended when the seconds intervened, a fencer called “Halt!” because of exhaustion, or an injury was received), or if it was for the far graver auf einen Gang, where the seconds stood back and the fencers were required to inflict an Anschiß—a debilitating wound of a certain depth in the chest or the face, or at least 3 minor bleeding wounds on the fencing arm.

Dr. Köhler was the more experienced fencer and held back, not pressing his advantage. But in vain: Erdmannsdörfer was out for blood. He pushed the attack, lunging again and again at the embarrassed physician.

Eventually, he lunged straight into the opponent’s blade.

The blade entered his lung at a depth of several inches: The classic Lungenfuchser—a perforated lung causing a pneumothorax and internal bleeding into the lung. Literally drowning in his own blood, Erdmannsdörffer “by midnight was a corpse, the doctor a murderer on the run”.

Erdmannsdörffer’s grave marker isn’t quite accurate. This was not a “Mensur” in the sense of Bestimmungsmensur — the arranged fight between fencer determined to be evenly matched by the officers of a dueling fraternity. This was a duel proper, albeit according to the students’ Comment. And really, Erdmannsdörffer had it coming… he provoked the fight and pursued it with more aggressiveness than the cause of action demanded—you can hardly call him a victim. (Even if that is now de rigeur…).

Deaths during duels and rencontres were more frequent and far more savage during the mid- to late 1700’s. Still, the death of the arrogant young pup Erdmannsdörffer was the last straw that broke the back of the 200-year history of student duels with thrust weapons at Jena. That year, under the guidance of Fechtmeister Friedrich August Wilhelm Ludwig Roux, even the last fraternities engaging in Stoßduelle switched over to the Hiebcomment (cut fencing) and introduced the Mensur proper using Schläger or curved-bladed sabers (“Krumme”).

Other than in France, thrust duels disappeared entirely from Germany since 1845. With the elimination of the last bastion of thrust fencing in Jena, thrust fencing in Germany focused on foil practice, in the French and, from the 1880’s, according to the new Italian manner. As the “Pariser Degen”, with its the foil-hilted épée blade, finally culminated in the modern épée, the dueling weapons of Germany became the saber and the pistol.

But I hear you ask: What about the Tumultus, the fifth fight scenario for German students?

We’ll leave that for a future edition of The Historical Fencer.

1 Faselius, Johann Adolph Leopold. Neueste Beschreibung der Herzoglich Sächsischen Residenz- und Universitäts-Stadt Jena, oder, historische, topographische, politische und akademische Nachrichten und Merkwürdigkeiten derselben, Jena: bey Joh. Gottfr. Prager und Comp, 1805.

2 “Allerhand: Der Student, das Philisterium und die Mütze”, Allgemeiner Anzeiger und Nationalzeitung der Deutschen, Jahrgang 1845, vol. 2, p. 270-71.

#Hookahmagic

Мы всегда с Вами и стараемся нести только позитив и радость.

Ищите Нас в соцсетях,подписывайтесь и будьте в курсе последних топовых событий.

Строго 18+

Кальянный бренд Фараон давно завоевал сердца ценителей кальянной культуры вариативностью моделей кальянов,

приемлемым качеством и низкой ценовой политикой. Именно эти факторы играют главную роль в истории его успеха. Не упускайте очевидную выгоду и вы! Заказывайте кальян Pharaon (Фараон) 2014 Сlick в интернет-магазине HookahMagic и оформляйте доставку в любой регион РФ. Мы гарантируем быструю доставку и высокое качество предоставляемой продукции.

https://h-magic.su/tortuga

Удачных вам покупок!