In this article, Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez from the Martinez Academy of Arms, goes through the etiquette of the 19th century fencing schools and present her translations of a number of historical rulesets. You can find the first part of this series here.

The fencing schools of the nineteenth century had specific codes of etiquette and civility that were in line with those of the schools of the eighteenth century. Good manners were either expected, or explicitly demanded.

Good manners and civility

The late nineteenth century Spanish fencing master Gregorio M. Dueñas entitles his rules, “Rules of Urbanity and Courtesy”. All his rules are about proper conduct in the fencing hall and in particular when fencing strangers. He writes: “do not practice any conduct that is not compatible with good manners and education.”

Italian fencing master Alberto Marchionni tells us that: “the fencing school requires decency and reciprocal respect like any other noble establishment.” The rules enforced a civility that went beyond good manners and addressed potential situations where a slight could be perceived.

Fencing master Barthélemy De Bast includes rules of this sort, thus preventing any possible conflict. He states: “When fencing, if one perceives that the adversary is becoming angry, pretend to be tired and end the encounter.”

In the same vein, fencers were expected to acknowledge touches received and not to claim touches denied by the adversary. Dueñas tells us that when beginning an assault, one should receive the first touch out of courtesy. The custom of picking up the adversary’s weapon (if one should disarm the adversary) and returning it to him reappears over and over within these rules sets. Marchionni explains the reason as to why this is important. The fencer “…must show thoughtfulness and pick it up in order to eliminate any idea of boastfulness.” Another notable Italian fencing master, Vittorio Lambertini, goes on to state that regardless of one’s title or rank, one should promptly pick up the weapon and rearm the adversary.

Safety in the salle

Considerations of safety are also an integral part of the rules. Students are required to have the permission of the master in order to assault, and are forbidden to fence without protective equipment.

Students are also responsible for having all the proper equipment. For example, Lambertini requires that each fencer have two foils, one or two masks, a pair of padded gloves, and a pair of low cut sheepskin shoes. The button of the weapon must be checked from time to time to make sure it is affixed properly. All equipment must be put away in its proper place, and when borrowing equipment it must be returned in good condition.

Why obligations and formality matter

There was also a specific protocol in place for the obligations of the fencers. Upon entering or leaving the school, fencers were obliged to greet the master and those present. However, they were expected not to interrupt a lesson to give their salutations. Also, they were required to remain quiet, so that the student or students could clearly hear the master’s instructions. Students were forbidden from critiquing the other fencers and giving them advice. Foils broken during a lesson with a Provost or Master were to be paid for by the student. Foils broken by a visitor were to be paid for by the person who invited them; foils broken by students were on the account of the person holding the broken foil.

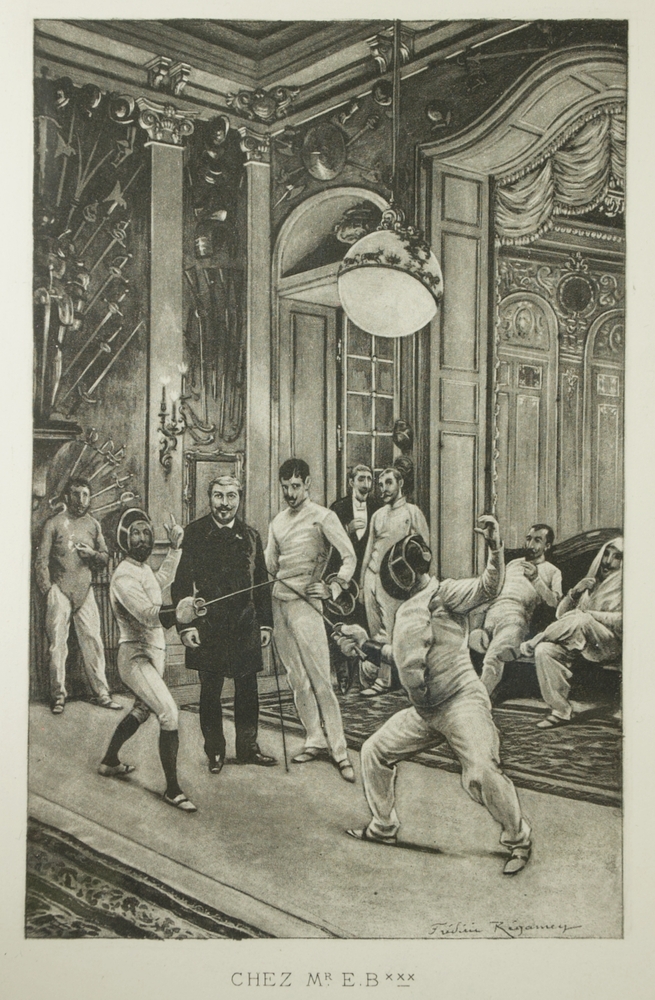

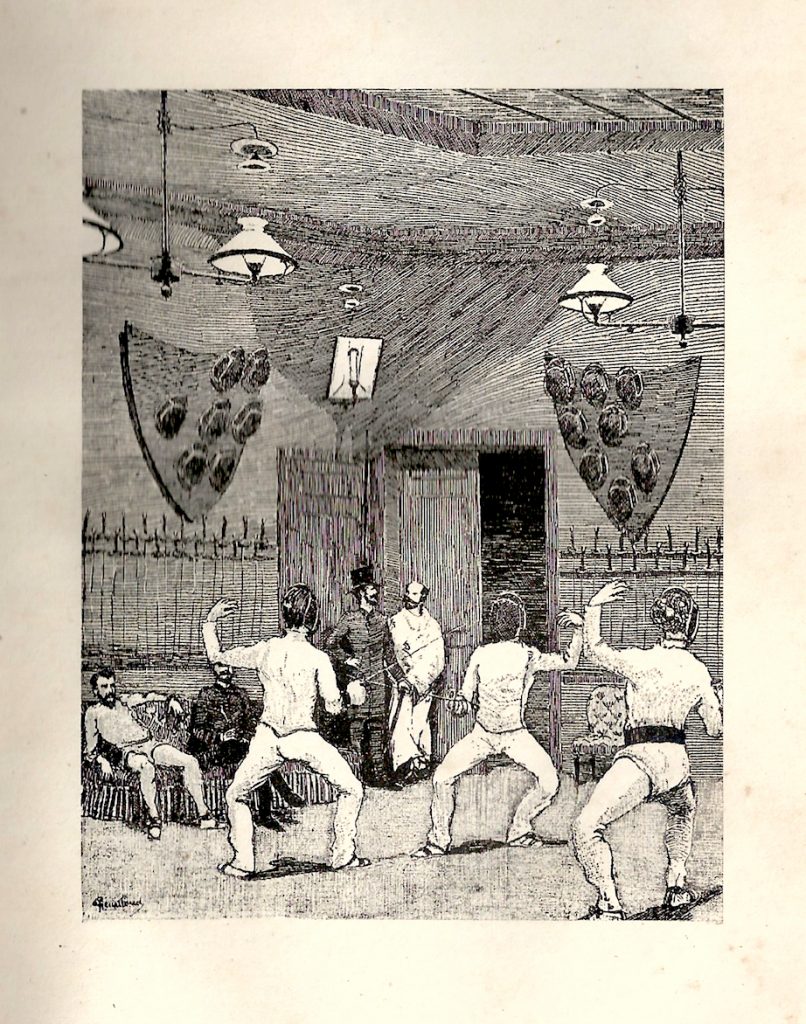

Just as had been the case in the eighteenth century, fencers were encouraged to visit other schools to fence with different types of fencers, test themselves, and gain experience. In mid-nineteenth century Paris, for example, rivalries grew between fencing schools and amongst the prominent fencers. Various schools held public assaults that drew large crowds. Also, events called Academiewere held in Italy, wherein assaults were held before the public, designed to allow fencers to demonstrate their skillfulness. Thus, commonality in etiquette throughout Europe and the Americas facilitated visiting any fencing school for lessons, or taking part in these various types of public assaults.

Translation of the rules:

The following are rules sets that clearly indicate the etiquette and protocol within the fencing schools of the nineteenth century.

Fencing rules of Mr. Francis George Bauge

Macon, Georgia USA, 1832.

- Gentlemen on entering the fencing room, are requested not to smoke, or spit on the floor

- No scholar, or visitor, may interrupt those who are taking lessons.

- Swearing, and all obscene language prohibited.

- Do not make sport of the awkwardness of new students.

- Do not play or romp in the room during school hours.

- Each student is allowed to invite four visitors but no student can admit the same four more then once.

- Parents and guardians can be admitted at all times.

- Do not set to with any student until your teacher takes off his mask and lays by his foil.

- On entering and leaving the Academy observe a military carriage of your person and the attitude of a soldier.

- One lesson will be given in each branch, every day. If a student misses a lesson, he will be permitted to take double lessons when he has time.

- No person in a state of intoxication shall be admitted into the room; and if he is a student he will be dismissed

- Any person taking the first lesson, will be held responsible for the whole coarse.

- Payment is not required until the termination of the coarse, and if Mr Bauge does not give full satisfaction students will not be compelled to pay a cent.

- Hours of teaching will be stated at the Academy.

- Neglect on the pat of the teacher, will release the scholar from the tuition money.

- The teach will not be held responsible for the neglect of the scholar.

- After course of any scholar has terminated, the room will always be open to him and the teacher will, with pleasure, practice with him free of charge.

- Ladies shall never be denied admission as spectators.

- Scholars are requested to be graceful in their demeanor, and to salute the audience before they commence their exercises.

- Students are requested not to put the button of their swords on the floor, or have their gloves and masks, or foils in any other than their proper place.

- Students are requested not to fence without masks, or gloves.

- If any student shall injure or deface the Academy, he will be held liable for such injury.

Bast, Capitanne De. Manuel D’Escrime. La Haye, 1836

Translation by Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez

Rules of the Fencing School

- No stranger can gain admittance to the school if he is not conducted by one of the students.

- When entering or leaving the school, greet the master and those present.

- Every student should have a foil, masque, glove and a pair of sandals.

- The student will take his lesson in turn when he is present and has two occasions (in which to take that lesson); any student entering into the school while someone else is taking his lesson, takes his lesson in turn immediately after that.

- Foils broken by the Master or by the Provosts of the school, while giving a lesson to a student or while fencing with him shall be paid for by that student.

- Before leaving the school everyone shall return their foils, masks, glove and sandals to their place.

- One should not use any of the fencing equipment belonging to others without permission of the owner.

- When one wants to hold the foil in an upright manner, it is forbidden to bring the button to the ground; it should rest on the foot.

- The students may never fence with each other without obtaining permission from the Master.

- It is forbidden to fence without a mask or glove, even in jest.

- When fencing if one perceives that the adversary is becoming angry, pretend to be tired and end the encounter.

- If while fencing, the foil or the mask of the adversary falls, one must pick it up and politely present it to him.

- One should never claim that one has made a touch when the adversary denies the touch and it is necessary to announce openly and in a loud voice that one was touched every time the hit arrives.

- All persons present shall answer the salutes of the fencers.

- Any broken foil will be on the account of the student who is holding the broken foil.

- The students will be polite to any strangers, but they may not present foils to them without the permission of the Master.

- When a stranger breaks a foil, it is on the account of the student who presented him the foil.

- One must abstain from smoking and indecent language.

- Fooling around is forbidden as it may lead to quarrels.

- For the same reason, it is forbidden to mock anyone, while the students are fencing, to make signs of approval or disapproval, and finally, to disturb them in any manner.

Marchionni, Alberto. Trattato di scherma spora un nuovo sistema di guoco misto di scuola Italiana e Francese. Florence, 1847.

Translation by Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez

Rules of Discipline:

To better serve simplicity I will reduce from the many distinct axioms, referring to the discipline and rules of the fencing school.

- The fencing school requires decency and reciprocal respect like any other noble establishment.

- It is not possible to determine the precise method of any Master in giving his lessons, which is subject to variances dependent on possible circumstances. However, generally speaking, it is usual to give three lessons per week occupying one hour per lesson including an interval of repose. In this interval the Master may give a lesson to another student that is to say a quarter of an hour rest for each.

- When someone decides to take fencing lessons, if a specific agreement is not made between the Master and student, the main rules should be remembered which establish a specific time for lessons, the student failing to arrive at the precise time, can not demand of the master that he takes care of him in another subsequent hour.

- When two students want to assault they will not be able to do so without the permission of the Master nor without being equipped with the necessary protection, namely the mask, glove, fencing jacket, cravat, and making sure that the foil has a leather covered button. Failing to take these precautions as they serve to preserve one from whatever misfortune would be an inexcusable carelessness and even more inexcusable if the master is not vigilant in order that these omissions do not take place.

- If in the assault one of the fencer’s foils should fall, the other one must show thoughtfulness and pick it up in order to eliminate any idea of boastfulness.

- Equally, if in the assault the foil blade remains bent it is indecent to fix the button of the foil on the ground in order to straighten it because the adversary could think that this was done with the intent to leave the imprint of the hit on his chest by means of the type of stain the button takes on when being rubbed on the floor.

- As is said above what a fencing school demands is mutual respect and all possible regard not only between the Master and his students, but also among the students. Now here I add that such regard should be rigorously practiced in a fencing school precisely to prevent all dangers and inconveniences to which one is exposed to in the management of arms. In as much as the purpose of the practice of fencing is not to make the young arrogant and bold; its’ intent in the encounter has an opposite goal, the Master should study with care the varied characters of his students and if needed, send away the most turbulent using all diligence in order not to permit villainous acts or whatever other actions that may incite strife.

- When it happens that the Master breaks one or more foil blades in the circumstances of the lesson (or the assault), in training his student, the student is obligated to pay for the blade that is broken. Equally, if not out of obligation, at least out of decency, it is the established custom that an intermediary inviting a foreigner, or whoever is not attached to the school break some blades, the burden of paying for them should be taken on by the person who invited them. When two students practice together, and they break foils, one does not look for the reason why they are broken, but the damage always rests with the one holding the broken foil in his hands.

Lambertini, Vittorio. Trattato di scherma teorico-pratico illustrato della moderna scuola italiana di spada e sciabola. Bologna, 1870.

Translation by Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez

Rules to Observe in the Fencing School

General Obligations

- All individuals that happen to be in the fencing school should comport themselves as civil educated persons.

- When entering as well as leaving, one is obligated to greet the persons that are in the room. Not those beginning and ending an assault.

- During the time of the lessons all bystanders should conduct themselves in a manner that does not prevent the student from hearing the masters voice.

- It is prohibited to practice or play with the weapons contained in the fencing room, without being secured with a plastron, gloves and mask, according to the weapon being used to avoid whatever incident.

Obligations of the Students

- Whoever desires to take fencing lessons should direct themselves to the master, with whom the day and time is agreed on, not the monthly fee that should be paid to him.

- Every student must provide the objects that are on paragraph 2; and missing these, cannot use those of others without their permission. (The objects are: two foils, one or two masks, a pair of padded gloves, a pair of low cut sheepskin shoes.)

- Students cannot assault if not given permission by the master, as he knows their abilities.

- It is the obligation of the students themselves to observe from time to time if the leather button covers the nail-head, otherwise they must refrain from fencing in order to avoid an accident.

- It is obligatory in an assault whenever one is touched to acknowledge the hit received by saying, “touched”; and to hold back immediate ripostes unless the situation is such that one could not hold off a hit.

- During an assault, if one of the two fencers comes to be disarmed, or his weapon falls, the other regardless of whatever his title might be, should promptly pick it up delivering it into to the hand of the adversary by the hilt, in order to avoid any idea of boastfulness.

- If it happens that the Master breaks one or more blades of the sword or saber, in the lesson or in the assault, when training his students, they are obligated to pay for the blade that is broken. Equally, if not out of obligation at least out of courtesy, it is the established custom, that, if an invited stranger or whoever is not attached to the school brakes a blade, the person who invited them pays for it. When two students practicing together break some blades, one does not look for the reason why they are broken, but the damage always rests with the one holding the broken foil in his hands.

- It is not permitted to smoke in the fencing school, except when the Master has a special place for conversations or a waiting room.

Dueñas, Gregorio María Ensayo de un tratado de esgrima de florete. Toledo, 1881

Translation by Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez

Rules of Urbanity and Courtesy

Every fencer should be aware of what we will present here.

– Before entering a fencing school, prepare to separate yourself form an exaggerated sense of pride.

– Do not practice any conduct that is not compatible with good manners and education.

– Ask permission of the professor to take a weapon and before placing it back in the armoire, give an accounting to the professor as to the condition in which you leave it.

– Do not touch the wall or the floor with the weapon, nor stain the button with substances that may mark the thrust on the adversary, because not only is this bad form, it may bring grave consequences.

– It is not permitted to have secrets or jokes that wound the individual pride, which is more susceptible in these kinds of practices than those of any other nature, thus avoiding lamentable consequences that this susceptibility may have.

– Indicate all of the thrusts received, bringing the left hand to the chest with sincerity, and not with embarrassment. Concede not only those that have really arrived, but also those that in all conscience would not have been parried, and if they were, it is due to chance. Similarly indicate those, that part of the audience may have believed were received; because whether indicated or not, the intelligent person that observes, knows if the thrust was good or not and in this way one can gain their sympathies. This is what one should seek in every assault because on being observed, a contestant glad of the attendance, fences better and the influence of this circumstance makes one see more clearly and assault with more care and success.

– All the contrary happens to the one who denies thrusts or commits other disagreeable acts, because his lack of prudence attracts the indifference of the public, his reason is obfuscated more every time and his blunders lead him to a complete defeat.

– If you fence with someone who is accustomed to not acknowledging the thrusts that he receives, since this is very reprehensible, even more so is to claim them, saying: “I have touched”, thus one must not ask, and although the adversary may not indicate them, or denies them, always indicate those that you receive. Also, do not attack while they are signaling but only after well-indicated touches, and we do not mean after signals or salutes, as the salute distracts too much.

– Even though the thrust has not been received in the chest, always indicate it by bringing the left hand to the right nipple, as if the touch would have landed there. For example, if it would have arrived on the thigh and you bring the left hand there it would appear to accuse the adversary of a defect. This in turn is very convenient to do when one fences with persons well known to you, so that they may study the manner to correct their errors.

– The strong should never abuse the weak, and if striving to go for many thrusts; it is proven that the sympathies of the public as in all aspects of life will always be inclined in favor of the least potent, especially, if he is attentive and at the same time modest.

– In the beginning of an assault one should be attentive to receive the first thrust, which is called “of courtesy”, this name is also given to those that conclude the assault. It also is the custom to say; “the last three”, from these one should endeavor to receive the last.

– If by chance the adversary drops his foil, it should be picked up and returned to him by the hilt, with a type of salute.

– Have much care, with one who is unknown, in the selection of a contestant, seeking to choose always from those that have more skill and knowledge, because no glory comes from defeating the conceited ignorant, and if by effect of education or compliance they emerge with airs, attributing to ignorance that which was solely gallantry, they offend the art and the fencer.

– When terminating all assaults, after removing the gloves the contestants should cordially extend their hands toward one another, out of courtesy and as a sign of no resentment.

Bonnefont, Gaston Les Exercices du Corps.Paris, 1890.

Translation by Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez

The fencing school must be considered as a meeting place of well brought up people, and fencing as the particular art of the gentlemen; so, the most scrupulous politeness most govern all the practice and the assaults. One most guard against mocking a clumsy person, and avoid disturbing the fencers who are practicing. If, by fighting against an opponent, one disarms him, one must collect his foil and handed back to him.

It is customary to remove your hat in a fencing school and not to smoke there.