The art of fencing in Europe has had a connection to urban life throughout its history. It’s primarily in cities that the guilds operated and where fencing became part of the urban life and culture. One of these cities is a true European gem even today… Prague – the capital of the Czech Republic. Let’s dig in to its untold role in the development of the German fencing arts

The city of Prague, founded around the 8th century during the reign of Premysl (the founder of the Premyslid dynasty)holds a legendary tale associated with its origin. According to the legend, Premysl’s wife, Libuše, prophesied that Prague would become a great city whose glory would touch the stars, prompting the construction of a castle near the Vltaba river. Over a thousand years later, Prague stands recognized as one of Europe’s most beautiful cities, boasting the largest castle in the world, according to the Guinness World Records. Throughout its rich history, Prague has served as the capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia, Czechoslovakia, and the Czech Republic, and at times, even the capital of the Holy Roman Empire.

But what is unknown to many, including local historians, is that the city played a major role in the development of the Germanic martial arts tradition and what we today call historical fencing. It is true that most fencing treatises known to us were written for the Germanic princes and dukes, and it was Frederick III who promoted the creation of both the Landsknecht and the Marx Bruder fencing guild. However, a later revival of the Art was centred not in Nuremberg, or any other city in modern Germany, but in the Kingdom of Bohemia, specifically in Prague.

The rise of the Federfechter

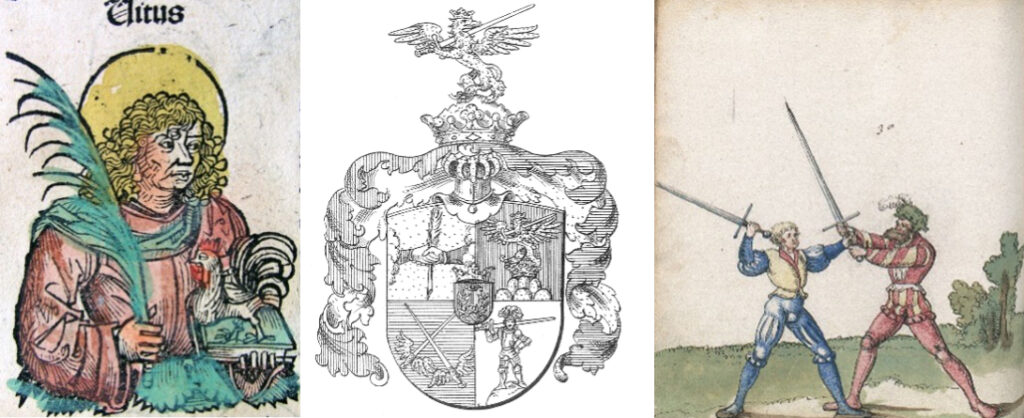

In the year of 1570 (according to Egerton Castle), a new fencing guild was founded in Prague: The Federfechter, or Freifechter von der Feder sum Greifenfels. The origin of the name itself remains unclear. Some scholars believe that it is related to Saint Vitus, to whom Prague’s Cathedral is dedicated, and who is often depicted holding a pen (feather) with his right hand and a book and a chicken in his left. Brothers Grimm speculated about the origin of the name, coming down to two different hypotheses, the first one being the custom of wearing feathers on the hat. This was a common practice at the time, highly popularised by the Landsknecht a century before. The other theory was that the guild might have originated from professional scribes. Regardless, the Federfechters grew to be a power in themselves and quickly rivalled the monopoly of the Marx Bruder as they were admitted by the council of Frankfurt in 1575.

Rudolf II and the Federfechter

A central figure for the revival of Prague was Frederick III’s great-great-great-grandson Rudolph II. In 1576, he breathed new life into Prague by relocating the imperial court to the city. Despite being considered an ineffectual ruler, Rudolf II’s patronage of the arts left a lasting impact. He sponsored numerous artists and curated an artistic collection that was highly esteemed during his time, contributing to the development of an artistic style often referred to as Rudolfine Mannerism.

And in 1607, Emperor Rudolf II officially recognized the Federfechter, granting them the authority to certify fencing masters within the Holy Roman Empire. A privilege previously only extended to the Marx Bruder, who were recognized in 1487.

The Dussack’s rise to prominence

Another significant contribution to the art of fencing from the kingdom of Bohemia is the dussack, which would become a signature weapon of the late Germanic fencing tradition. The word dussack apparently originates in the Czech Tesák, meaning fang, and might have become popular among German speakers during the Hussite Wars in the early 1400s.

Throughout the 15th century, German fencing masters predominantly used the Messer as the weapon of choice for teaching the use of one-handed weapons. The peak of this practice was arguably marked by master Johannes Lecküchner’s treatise Kunst des Messerfechten in 1482. This treatise is the most extensive Messer manuscript ever created and it became the reference source for later German masters.

However, by the beginning of the 16th century, there is a shift from messer to dussack. In 1516, Freifechter André Paurenfeyndt’s published his work Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey, dedicated to Cardinal Matthäus Lang von Wellenburgwould. In this book, he teaches the use of messer, but illustrates it with wooden dussacks, and interchanges messer and dussack across his technical descriptions.

The dussack’s popularity continued to rise during the 16th century, with illustrations of the weapon regularly appearing in fencing schools’ representations. It also became a common weapon for fencing guild gatherings. In what is likely the most important treatise on the use of the dussack, master Joachim Meyer introduced the weapon in 1570 as the source for all one-handed techniques within the German tradition, similar to how Johannes Lecküchner had done a century before with the messer. Interestingly, a record from 1579 (only nine years after Meyer’s publication), mentions the delivery of 700 Dusäggen in preparation for the Long Turkish War, initiated in 1593 by Rudolf II to unify Christendom against the common enemy.

In 1679, master Theodori Verolini published the last known treatise discussing the use of the dussack, taking inspiration in Meyer’s work. But its use survived at the very least until the late 1700s as a practice wooden weapon and as a complex-hilt steel sabre. According to Egerton Castle, dussacks were even used by the French Navy up until the 19th century.

Pod šable – a traditional Czech point-and-hilt dance

The use of the dussack does however persist into modern times within the Czech Republic, albeit not as a weapon but as a dancing tool. Within the extensive tradition of European sword dances, we can find pod šable from Strání, a regional dance in which a group of people dance waving wooden sabres, or dussacks, that look very much like Meyer’s illustration from his 16th-century works. This dance is part of a longer ritual that begins with singing and then changes to a hilt-and-point sword dance of five dancers performing simple figures such as clashes of swords and passing under or over the sword. Later in the dance, more singing is done, and the dancers break out and dance with female partners.

A few final words on the importance of Prague

To conclude, from its foundation in the 8th century by the Premyslids, through its golden age under Charles IV, proto-Protestantism, the Hussite Wars, infamous defenestrations, Habsburg rule, and the Thirty Years War, Prague’s vibrant history has intertwined with the development of historical fencing. Understanding this rich tapestry of combat and violence is crucial to appreciating the role it played in shaping the Holy Roman Empire and the Germanic fencing tradition.

About Arturo Camargo

Arturo is a sports and martial arts enthusiast with almost 20 years of martial arts experience. He is also a certified sports trainer by the Sports University in Mexico and has a History degree. Arturo expends most of his time teaching, researching, and interpreting historical martial arts. In 2008 he founded Krigerskole, now one of the largest HEMA schools in Mexico. He is also a co-founder of the Unión de Artes Marciales Europeas (European Martial Arts Union), an organization dedicated to the reconstruction, practice, and diffusion of HEMA in Mexico. As an instructor, his main focus is on the German longsword, messer and ringen; he has presented workshops in several events both nationally and internationally, among them Fechtschule America, Combat Con and the ILHG. As a fighter he is a four times National Champion and several times international medalist and has coached another four National Champions.

Follow him and learn more here:

www.krigerskole.com

www.facebook.com/krigerskole

www.youtube.com/c/krigerskole

www.instagram.com/krigerskole

https://www.facebook.com/A-Knights-Training-307491026339632

References

Säbel, ‘Dusägge’, Deutsch Ende 16. Jahrhundert”, Waffensammlung Beck, Inv-Nr.:Be 10.

Castle, Egerton (1969). Schools and Masters of Fence, from the Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century (3rd ed.). York, Pa.: G. Shumway. ISBN 0-87387-030-1. OCLC 59772.

Anglo, Sydney. The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000. p 46. ISBN 978-0-300-08352-1

http://www.rapper.org.uk/relations/czechslovak.php