What is a fencer? Part II

What is a fencer? Part II

The sword is one of the most powerful symbols of our culture. But how does the sword and fencing fit into our modern world? And what defines modernity? Today, we take a deeper look at what it means to be a fencer. We dive into the soul of men to get a glimpse of the ancient battle between good and evil. Let there be light!

His education had been neither scientific nor classical – merely “Modern.” The severities both of abstraction and of high human tradition had passed him by: and he had neither peasant shrewdness nor aristocratic honour to help him. He was a man of straw, a glib examinee in subjects that require no exact knowledge (he had always done well on Essays and General Papers) and the first hint of a real threat to his bodily life knocked him sprawling.

– C.S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength

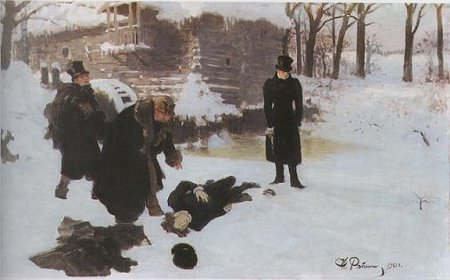

I remember that my limbs felt weak, and their weakness spread into my mind. The boy I once was – the skinny boy with all the internal voices of pacifism and fear, of moral indignation at the very thought of violence – filled my existence. That boy stood there, facing a darkness he was not equipped to handle. Though my body had transformed into a manly shape, my mind was lingering in adolescence. Never put to the test.

I could easily have acted. I could have handled that situation. I could have struck. But I was not prepared. There had been no trial of manhood, no true test of my virtues. When facing the “real deal” I was unprepared. I had been taught that all the virtues needed to handle this situation were in fact vices. I was raised in a culture that abhorred violence.

I blocked the first blows, reflecting on how I could strike back, but I hesitated, preferring his violence to my own. Even as the first blow hit my face, fracturing my nose, I could not bring myself to break the taboos which endless teachers of the modern world had ensured me was the righteous path. Instead, I pleaded hopelessly, realising how futile abstract arguments were in the face of someone in touch with his inner darkness. What a poor excuse of a man I was.

The fall into modernity

I am torn, like a herb from the soil.

– Erik Axel Karlfeldt

If you stand among the remains of the untold millions of dead in the catacombs of Paris and imagine all the lives that they represent, you will be filled with humility. Now imagine the brevity of your mind in the darkness that is our empty universe. Imagine all the things that you hold dear, all the people surrounding you, all the events that you recollect. Imagine them ended. Even more than that, imagine everything long lost – ancient civilisations, buildings, art, music – obliterated into nothingness in the vast eternity of emptiness that is time and space.

Such is the objective realisation of the modern world. That idea is the collision between the subjectivity of being human and the dead objectivity of physical reality. It means that Mankind is no longer part of a greater scheme; we are simply organic matter with an unfortunate consciousness that has to find its own purpose in order to cope with mortality. If you despair because of this, you are not alone; these feelings are a by-product of the modern worldview.

Modernity means we have truly made the shift to an androcentric perspective. We are at the centre of everything, and our new tool to explain the world is science. In this new world view, we reduce life into quantifiable subjects, because science only deals with small, measurable portions of reality. And we make great progress forward, going farther than we ever thought possible. But we lose our connection to the past at the same time.

It is an ironic twist that in putting Man at the centre of creation, we have done so by creating the most distanced way of describing reality that is humanly possible. Brian Cox noted, “We are the cosmos made conscious and life is the means by which the universe understands itself.” How strange, then, that we have abandoned our inner worlds and conformed instead to the objectivity of scientific research, letting that perspective entirely dominate our societies.

We look at the universe and acknowledge that which can be proven according to Cartesian logic and empirical standards, and it gives us great knowledge of things. But at the same time our own stories are transformed into fiction, and become something less than truth in the process. But our stories are not lies; they are simply subjective. And if we are indeed the only subjective beings, then they are the only truth that matters when it comes to describing the human experience.

Modern Man tries to explain the human experience with the language of scientific rationality, as if the death of God not only robbed us of a greater meaning, but also of the richness of our language. We face a reality where modernity cannot describe the human experience without reducing it to something hardly worth anything at all. This kills the bond with our ancestors, who did not describe the world in absolute terms or objective truths, at least not in the way that we do today.

Maybe the reasons for this can be traced back to the shift to monotheism. The ancient world saw the gods as different facets of reality, but the monotheistic God was a single truth that didn’t accept other realities. When God finally died, the monoculture survived him, and the axiom of monotheism was applied to the new world. Only without God.

A world reborn

The realisation that the universe is indifferent to the injustices of the world can lead us down two false paths: One is the cynicism of relativity, in which we accept the death of eternal truths, values and traditions; this leads in turn to moral apathy, narcissism, and shallow materialism. In this despair it is easy to superficially mimic tradition in a trivial mockery of what it once was, which in truth only is another manifestation of a modern mindset. The other is the path of blind reaction, which leads in turn to unthinking glorification of the past, and social ills such as fundamentalism and extremism. The remedy, as ever, is the middle path, which leads us to insight into the true purpose of values: To be a defence against indifference.

The Enlightenment aimed to liberate Man from the chains of an oppressive God, setting us free in the universe. But the universe’s indifference tells us that we are the only conscious beings, and our experiences are but brief moments lost in the vast aeons of the Cosmos. What then, can describe our existence in a way that resonates with our potential? What can give us purpose and meaning?

I trow I hung on that windy Tree

nine whole days and nights,

stabbed with a spear, offered to Odin,

myself to mine own self given,

high on that Tree of which none hath heard

from what roots it rises to heaven.– Hávamál

For some, who can still believe, the answer is Faith. But how can a God that we never see or hear, and who does not intervene in our lives, give us meaning? I don’t believe that a God is necessary, but at least the notion of God kills the idea of relativity, since it means that there is an eternal truth. Yet the same result can be achieved if we simply accept the subjectivity of experience. That is, by accepting that the subjective worldview – the ways in which Mankind has described reality in legends, stories and traditions – is a valid and true perspective, simply because it is ours. Regardless of scientific progress, we still must make our way through the cycle of life, as our forefathers did: Birth, adulthood, marriage, death. Religion provides traditions and rituals to help us cope with these facts of life.

The Norse called their religion Siðr, which basically means “tradition”. That tradition showed how you should handle your dead, live your life, treat your neighbours. In the Norse poem known as Hávamál, religious mysticism is intermixed with practical advice for everyday life. Siðrdidn’t require belief in God; in fact, there are examples of Norse atheists. We are humans and our traditions and inner worlds are our own. We need not give them up because we don’t literally believe that Thor is angry when there is thunder, nor that God created the world in seven days. The mysticism of our ancient beliefs describes a subjective reality that can hold meaning to us, even if it is not an absolute, objective truth. After all, if we could only describe reality with logical arguments, there would be no such thing as poetry.

I understand that I have taken this reasoning far into the domains of religion, but it is inevitable when discussing modernity in contrast to older societies. I do this because, for me, it is clear that tradition is a way to stay in touch with our ancestors, and I believe this worldview is pragmatic. It releases Mankind from the shackles of modernity, and it combines the traditional worldview with the humanist realisation that we are the purpose of our own world.

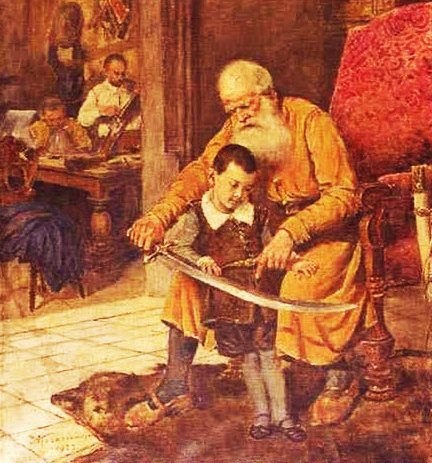

A society that is not rooted in its own tradition has lost its way. But it has to be tradition that is living, not just worshipping the past. As it turns out, our ancestors can teach us how to live well, how to handle the twists and turns of life, far better than modernity can. After all, it is wisdom based on 200,000 years of Mankind’s experience.

Tradition is the spreading of fire and not the veneration of ashes.

– Gustav Mahler

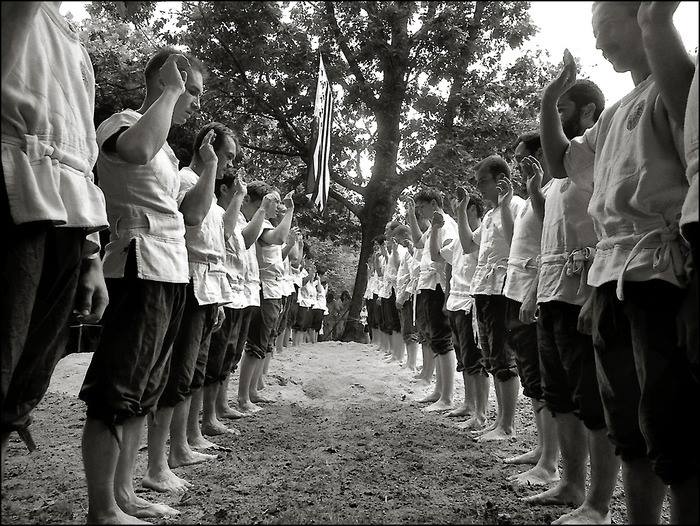

Rites of passage

In traditional societies, there were ceremonies for each milestone in a person’s life. Many of these customs seem irrational to the modern person. Why do we really need them? When we marry, why does the father walk his daughter down the aisle? Why marry at all? Why wash the dead? Why pour water over a baby’s head? Why pray or give thanks before a meal? Why think about our loved ones before going to bed? Why gather the family, prepare meals, and visit the cemetery to remember the dead?

The basic assumption of modernity is that the latest is the best. Constant development and change is glorified because it drives us forward. But the price for modernity is rootlessness.

Traditions, on the other hand, have value even if they are not rational, because they pass down knowledge over generations. They are mnemonic verses of what it means to be human, and they used to run through society and life like a metric verse. We are born, we reach adulthood, we choose spouses, we have children, we die.

If we do not stop to celebrate these things, every day turns into a bleak Tuesday. The prayer at dinner means we take time to reflect. The prayer for loved ones means we stop to think about them. The prayer for help or strength means we define what is important. If we get rid of these things, we reduce the human experience. We don’t have to believe in God to accept the importance of that. But in modern society we are abandoning our traditions, or taking them less seriously, so their meanings are lost upon us.

The noble man should either live with honour or die with honour. That’s all there is to be said.

– Sophocles

Cut off from our past, we don’t grow up anymore. We move through the world as children who do not celebrate life. And we die like weaklings who meant nothing to the world, reduced by modernity to biological waste. We are caught up in our narcissism and strive for eternal youth, because those who come after will discard us like yesterday’s paper. The most famous among us are those who display the most superficiality, who own the most toys. We compensate for the shallowness of modernity by indulging in an insatiable materialism.

Going back to the violent night where we began: It took me years to accept, but that was when I realised I was weak. Not physically, but mentally. Society had not prepared me to cope with violence. I had experienced it before, but I had not learnt to handle it. This man was a professional criminal, older and bigger than me. When facing him, I did not see him as an opponent, I saw myself as a victim. I was not prepared to fight him. I was frightened by his appearance, because it told me that he was a person with a close relationship with violence. He represented a darker side of Mankind. And who was I? In the face of real violence, my false front was exposed. I was prey.

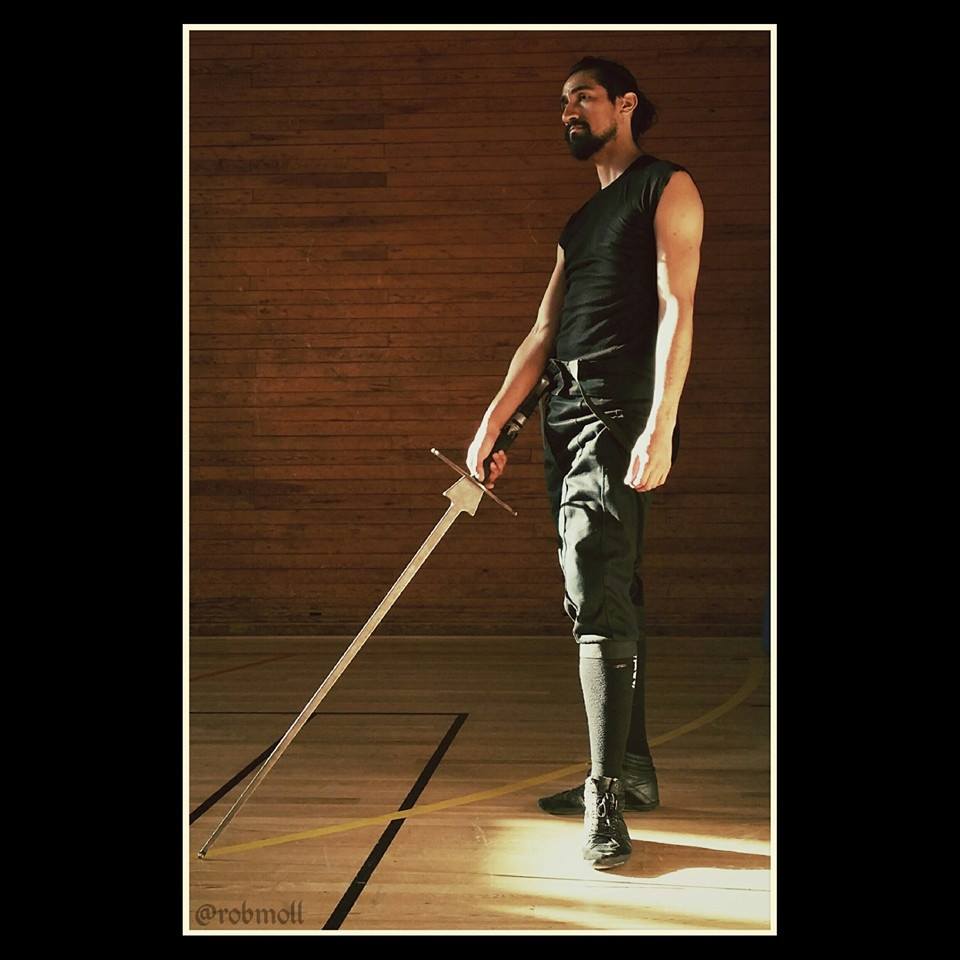

This is where I believe fencing plays a critical role in releasing us from the grasp of the modern world. For me, HEMA is a way of rekindling a fire. I sense that the current generation of modern people – brought up in the age of television, advertisements, and peace (for most of us) – are unconsciously searching for something more. And whether we are aware of it or not, that is the reason fencing holds such appeal to us. The sword represents a practical way of approaching our history and connecting to a world that we are missing, a way of attaching the lonely atoms that we consist of to our ancestors and thus growing back into a whole fabric again. To truly understand what this means, we also have to accept a very anachronistic aspect of fencing: The notion that it is both a test of our worth and a way to prepare ourselves for death.

Fencing makes one who can do it well

Into a formidable and capable man

Well-proportioned and sturdy

Light, fit, and nimble – ready for anything

Courageous and undaunted against the enemy

Valiant and stout-hearted, daring manfully

Bold in war; eager to win praise, honour and victory

Emboldening hundreds around him with ease

He makes you marvel at his fencing skill– Christoff Rösener, 1589

When Modernity falls

Modernity tells us to be selfish, because there are no eternal values. It tells us to protect our lives at all cost, because when we die it is final. The only value is that which we personally see fit to value. Of course, since we really haven’t changed as humans, we still intuitively understand that this isn’t entirely true. We are not isolated ships lost at sea. We are brothers, sisters, children and parents. We are our cultures and our nations. We also inherit our existence from our ancestors, and one day we will be dead regardless of what we do. But we still want to be remembered as great people:

| Deyr fé, deyja frændr, deyr sjálfr et sama; ek veit einn, at aldri deyr: dómr um dauðan hvern. |

Cattle die, kinsmen die you yourself die; I know one thing which never dies: the judgment of a dead man’s life. |

Traditional societies had rules that taught the individual how to be valuable to others. In fact, the individual’s respectability depended on it. One should be honourable, steadfast, reliable, true to his word, self-sufficient. We try to convince ourselves that this is no longer true, that we are great just the way we are.

But of course, we all value people based on the same things that we always did: We value providers, protectors, entrepreneurs, doers. We pity or despise those that cannot live up to these ideals – as we should. We may say that we are all equal, but if we are honest we know that equality does not exist, and that this is a good thing. If we don’t have ideals to strive for because we are all equal, then why do anything at all? We don’t have to better ourselves; we are all naturally good, right? Absolute equality means never even trying to set the bar for fear of hurting someone’s feelings of inadequacy.

It is a cold, hard fact that many of the things that we succeed in accomplishing are really not worth much at all. The ideals of the modern world are often fairly useless, especially when facing gaps in civilisation. The selfish, weak modern man can write an article (like this one), be an authority on the brewing of IPA, or whatever is trending at the moment, but when the veneer of civilisation breaks, he is helpless. We used to be held to a much higher standard. If the modern man runs from a robber it is not seen as an act of cowardice. In past times, such a thing could mark you for life. When Döbringer says it’s not an act of cowardice to run from four to six enemies, he is also saying that it is an act of cowardice to run from one enemy. And that person was armed with a sword.

The noble soul has reverence for itself.

– Nietzsche

What we see in this example is honour. If you are a man, you are supposed to be able to deal with threats and crimes against you and those belonging to your household.

Of course, not everyone will be able to live up to this honourable ideal. It is there to encourage you to live up to it. If you don’t, you will be judged by society. This breeds sturdier people. When the thin veil of civilisation falls, even if it is just on a night out when you happen to get into trouble with a random criminal, it is this type of sturdiness that is needed.

HEMA: Recreating more than the art of fencing

I believe that a lot of people practicing HEMA see it as more than mere recreation. Within our community, there is an understanding that the sword carries meaning, and without that meaning these arts amount to nothing. We can read about it in the sources: If you are full of fear, do not learn to fence. Be manly. Be knightly.

It is safe to say that a lot of us were drawn to the sword not because we wanted to learn a specific technique, get in better shape, or win tournaments. We were drawn to these Arts because of what the sword represents. HEMA is not only a way to recreate lost martial arts, but also a way to learn from an ancient culture so that we become better people. Stronger people. Less modern people. I believe we can help each other by promoting bravery, respectability, courage, and honour, rather than simply grafting modern values onto fencing. There is undoubtedly room for modernity too, but we should be conscious about what modernity means and why we might want it. We should only allow it in the door when it serves a purpose. Even then, we should remain vigilant to ensure that it doesn’t corrupt what we do.

It is impossible to recreate these martial arts in their entirety, because they existed in an historical context; the same goes for the values of the past. We can’t and shouldn’t throw away all aspects of modern society. A tradition is always something living. It changes over time and is applied organically. It’s not a stale preservation, a freeze-frame in time. But knowing our roots and bringing back positive aspects of our historical martial culture can have profound impacts on how we look at fencing and life.

Bringing back the nobility from within

There is, and always has been, a connection between the sword and nobility. Even though the sword has been used by most social classes, it has a special connection to the aristocracy, or at least to aristocratic ideals. The sword is an honourable weapon and fencing is a noble pursuit.

I have spoken about this before, that there are aspects of how to behave and how to act which I believe should be promoted within HEMA. But I would like to take it even further, that we accept some of the ideals of fencing tradition and internalise them to see where that leads us.

These ideals revolve around values and traits such as honour, courage, strength, justice, temperance, wisdom, intelligence, wit, respectability, and so on. However, I don’t think these are things that can be precisely defined or measured in a modern reductionist way; rather, they are things to aspire to. The essence of nobility is not to have a quantifiable measure of these traits, but instead to hold ourselves to a higher standard that also means responsibility – Noblesse Oblige. We can absolutely demand that inclusion into our social settings means that our fellows display traits that we hold dear; but more than that, we should always push to better ourselves, to act in a way that is useful to others and to make sure that we focus more on improving ourselves than on criticising others.

In this sense, I believe fencing can truly become a language to understand history. More than that, it can serve as a bearer of tradition and meaning into the modern world.

In conclusion, HEMA represents a return to martial traditions and values that fulfill important needs left unmet by the modernist worldview. It helps us connect with our ancestors, creating a feeling of oneness. It armours us against the despair, cynicism and moral apathy of modern life. Finally, it equips us with warrior virtues that we need when the veneer of society breaks down, by teaching us to have courage, fight well, and die honourably.

Anders Linnard

Gothenburg, Sweden

November 2014

Thank you!

Matt Galas has helped me immensely with editing, proof reading, discussing this article and finding images. All remaining flaws are entirely my own doing. Matt, your patience and knowledge are incredible.

I also wish to thank a special bunch of fencing Brothers. You know who you are.