Part One: An Introduction and a Summary of the Old Interpretation

Update: April 7th, 2022

From its creation, this paper’s intended purpose has been to dispel confusion and promote clarity of the subject matter; but hitherto it has not sufficiently brought that purpose to fruition. This is because our paper’s inception was flawed, and despite the author’s mostly good intentions, not all of the reasons it was created were good ones. When we allow passions and ego to affect our work, both we and our work suffer for it. This message is written in good faith to right the wrongs of our paper as it was originally released. Scorn and malice are diseases often born of a sense of injustice; but this is no justification for their existence. In their short-sightedness, they stop ahead of their rightful course further on towards understanding and compassion. Although a diseased sapling may begin to recover and eventually outwardly grow true, its core is nevertheless ever twisted and rotten, and this will be made readily apparent by the fruit which it bears. So was it with this paper, that although we, the authors, attempted to cover the corrupted foundation of our paper with courtesy, it shone through clearly to those whom we wrongly offended. While certainly not fully conscious of our actions, nor of the effects they would elicit, we were partially aware this throughout the process, and we worked to lessen any damage they would cause before our paper was released. Our efforts in this regard were clearly not enough, nor could they ever be, and it became clear as time went on that an explanation and an apology would be in order, since no amount of alteration may erase the underlying sentiment of this paper.

We cannot change the past. but we can accept our part in what has transpired, and admit our mistakes so that neither we, nor anyone else who observes them may ignorantly repeat them. Working towards this goal, I want to apologize on the behalf of the authors for any and all wrongdoing on our part. I admit that a desire for my own thoughts and opinions to be heard; a desire for justice for others whom I thought were wronged; and a desire for revenge against those who transgressed against me led us initially down a dark path which has caused a great deal of strife and confusion, spoiling and besmirching the reputations of both those who study Silver’s works and the Science which we love. I apologize that it has taken until now for me to find the words to say this, and I beg forgiveness for the damage that I have helped to cause.

In the spirit of humility and love, I have decided to remove this article in its original form from SVSOD’s website. In a time to come, as allowed, I plan to release a new version of this article which is premised upon cooperation, openness, and truth, one which may treat the invaluable works of George Silver properly, which reflects all of the respect due to him. With this I hope to right the wrongs I have helped to create, and not carry on Silver’s legacy of division, but to glean and share his underlying and true message; that of knowing and embracing whatever peace is possible in this harsh world.

Thank you to Stephen Hand, Paul Wagner, Stoccatta, and all of their friends and allies for all that you have done, both in keeping Silver’s teachings alive, and in helping to remind me of my humility. I only wish you joy and success, and I hope that some day we may work together on realizing our goal of making more people aware of this wonderful Science of Defence.

Your friend,

Cory Winslow

Take not arms upon every light occasion, let not one friend upon a word or trifle violate another but let each man zealously embrace friendship, and turn not familiarity into strangeness, kindness into malice, nor love into hatred, nourish not these strange and unnatural alterations.

– George Silver

A History of the Modern Controversy

“I have admonished men to take heed of false teachers of defence, yet once again in these my brief instructions I do the like, because divers have written books treating of the noble science of defence, wherein they rather teach offence than defence, rather showing men thereby how to be slain than to defend themselves from the danger of their enemies…” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

George Silver’s writings [1] have been a source of contention since their creation, having come about largely as a reaction to what Silver viewed as dangerous foreign methods of fencing, which were quite popular in England at the time. Recent history has seen a renewal of the controversy surrounding this work, although now being of a somewhat different nature. For the last twenty years there has prevailed a single, largely uncontested interpretation of George Silver’s True Fight, promoted by the majority of the relatively few modern followers of Silver’s work. The efforts of these individuals in championing Silver’s method are greatly appreciated, however, with the recent availability of a much wider range of source material, as well as the emergence of a new generation of historical fencing researchers, an alternative interpretation of the True Fight of George Silver has emerged, one which better and more completely explains Silver’s principles as originally written.

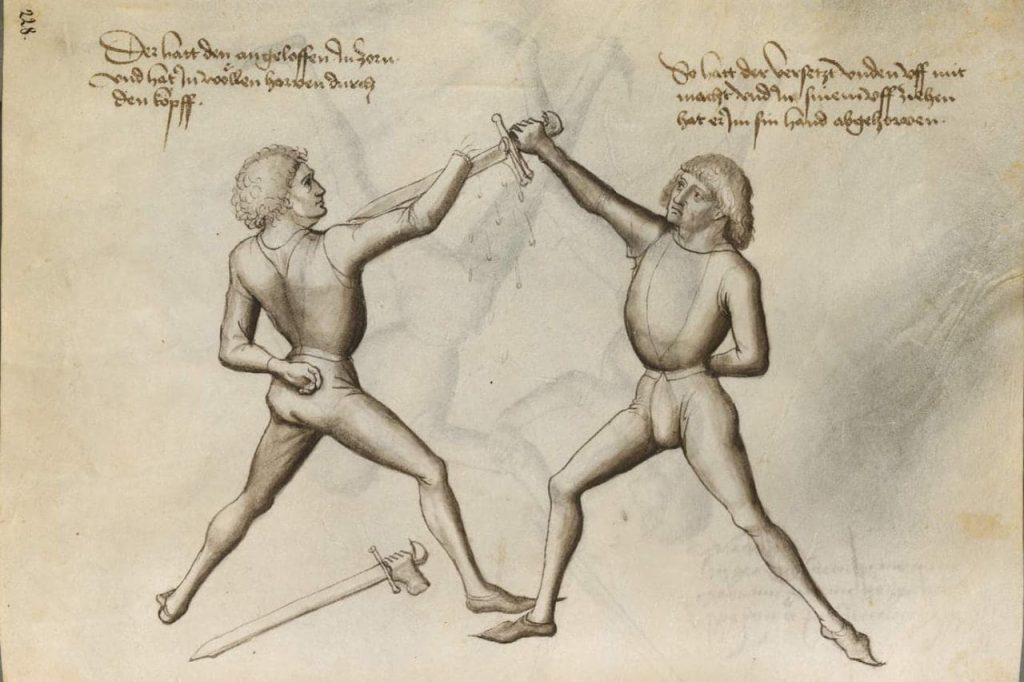

The first iteration of an alternative interpretation of Silver’s method was proposed by Martin “Oz” Austwick in the early 2010s. His was a lone voice, however, and those who claimed authority in understanding Silver, holding on to their old interpretation, largely drowned him out, though he never gave up the debate. In 2018, dissatisfied with our practice of the Kunst des Fechtens of Johannes Liechtenauer over the past fifteen years, we began to look into Silver as an alternative system, and were amazed at what we found in his writings. Like many others, we were familiar with the old interpretation of Silver, never having heard any competing theories, but what we saw in the source material itself, gleaned with the help of our combined decades of experience in Martial Arts, was nothing like the mainstream theory. We immediately made a video documenting our initial findings, the commentary thereon soon making us aware of, and putting us in touch with, Martin Austwick, with whom we confirmed our shared interpretation.

In late 2019, Vincent Le Chevalier released an article [2] suggesting the very similar conclusions to which we had come, conclusions which were very different from the old, mainstream interpretation of Silver’s method. A very public attack and defense of Vincent’s article ensued in which we took part, defending Vincent’s ideas as well as our own. During this time, several other researchers, some influenced by Martin, and others who reached their conclusions independently, contacted us confirming that they agreed with our alternative interpretation of Silver’s method. Finally, after private conversations with and receiving encouragement from several well-known researchers from such diverse Historical European Martial Arts traditions as the Bolognese Tradition, German Kunst des Fechtens, and Spanish Destreza, we decided to write this article explaining our alternative interpretation of George Silver’s method, in hopes that it may reach those HEMA practitioners who would benefit from understanding it, as well as shed light on a much maligned and misunderstood, though highly valuable, Science of Defence.

Why Silver Matters

“Ever shun all occasions of quarrels, but martial men, chiefly generals and great commanders, should be excellent skillful in the noble science of defence, thereby to be able to answer quarrels, combats and challenges in defence of their prince and country.” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

The value of Silver’s work is twofold, based on the contents of his treatises, and also on who Silver was, which greatly impacts the importance of his writing.

You should care about Silver because:

- He was a member of the Gentry [3], and as such would have likely received a martial education that was different from the middle-class London Masters of Defence, which had been given legal recognition by King Henry VIII, who had admired similar institutions in the Holy Roman Empire [4]. However, fencing masters were not always highly regarded throughout Europe [5]. The fact that a man of Silver’s standing in the society of the time published a treatise on fencing is something of which to take note.

- Silver was dissatisfied with the growing influence of Italian fencers and urged his readers to stick to a possibly older, native style of fencing; one with a clear focus on self-defense [6]. In doing so, he was not only lamenting the weapons and tactics popularized by certain Italian masters, but the culture of illicit dueling that these Italians were spreading throughout Europe, a complaint that he was not alone in making [7,8].

- The martial system that Silver recorded is unique among all others currently known. Some of his terminology is shared with some later English sources, and there are similarities that you would expect to find in all related arts, but there are also key differences that set Silver apart from any other source.

- Silver’s system emphasized the management of distance and timing and paired this with simple though effective actions, rather than involving the complicated or proprietary techniques found in some other sources.

- While Silver is not the only source to explain the role of distance and timing in fencing and how to use them to advantage, he was one of a very few non-Italian sources to do so comprehensively, as well as being one of the earliest. Since most of our modern understanding of timing and distance in fencing comes from Italian (and Spanish) sources, and since Silver’s treatise is largely about pointing out flaws in the teachings of Italian fencing masters [9], this makes Silver an invaluable source for understanding the nature of fencing as it existed before, or at the very least in opposition to, the spread of the Italian methods.

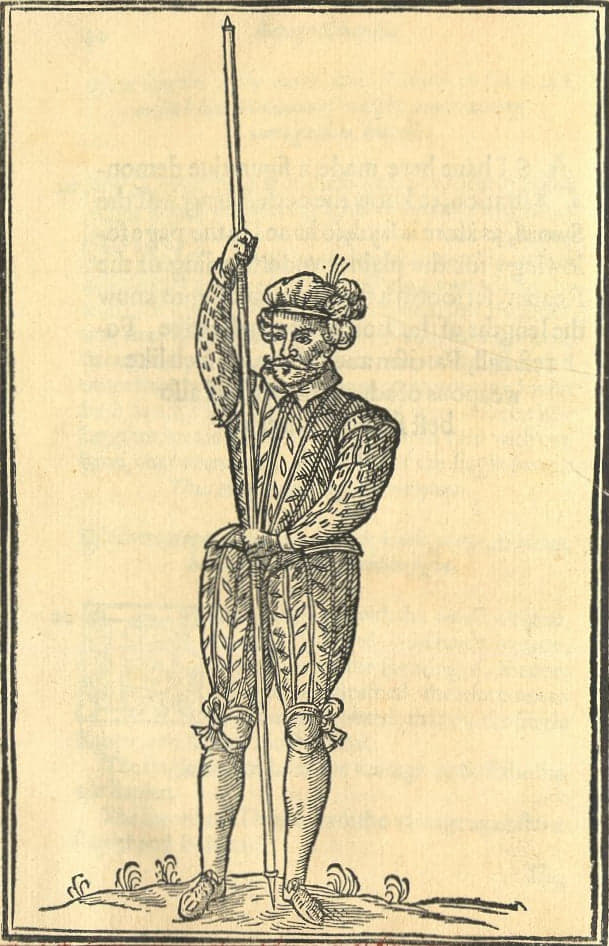

- Silver is one of a very few sources that delves deeply into the relative properties of various weapons (which weapons have the natural advantage when facing other types) and covers a wide variety of weapons, including polearms.

A Brief Summary of the Old, Established, Interpretation

“Truth is ancient though it seems an upstart.” – G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

(Note: We submitted this section of the article to Stephen Hand for his review and approval as we did not want to misrepresent his views. Stephen was gracious enough to oblige us and requested some clarifications, which we implemented. We are very grateful to Stephen for his assistance.)

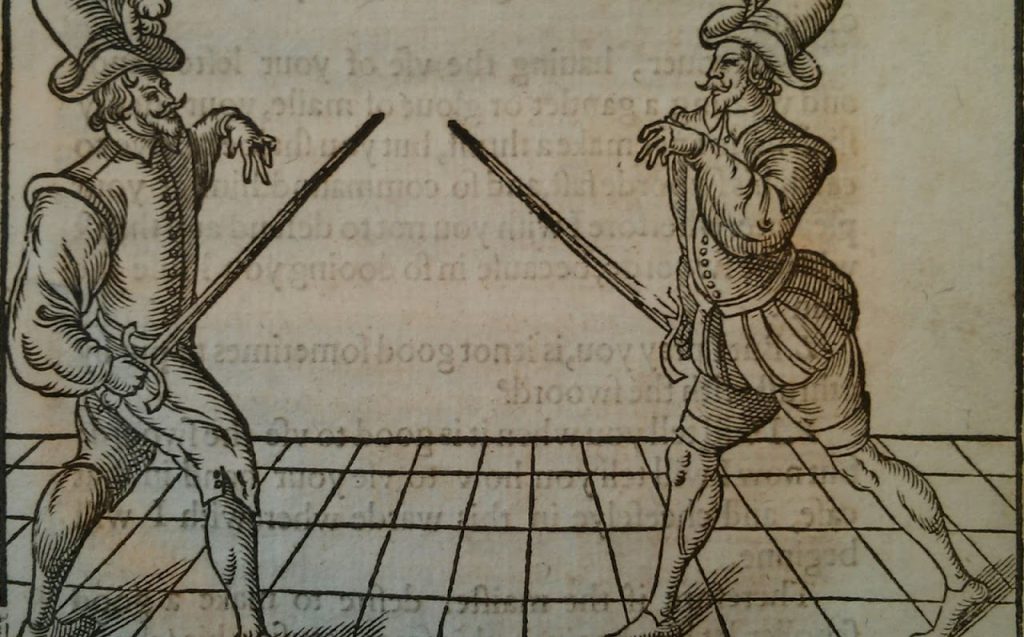

The widely established and accepted interpretation was initially put forth by Stephen Hand at some point in the 1990s, before the publication of his book, English Swordsmanship: The True Fight of George Silver, in 2006. The cornerstone of his interpretation is that the hand must move first in all actions. Most notably, this means that when you attack from a distance at which a step is required to reach your adversary, you must always move your hand first so that your sword moves before you and becomes your shield, clearing a path of safety for your body to move behind. But because the hand is faster than the foot, and would otherwise finish its attack too soon, before the body is brought into range with a step, Hand says that you should slow your hand, thereby giving it the freedom to act independently of the foot.

This does not mean that you move the hand fast and then slow it, but as Hand explains, “I move my hand at a steady speed that will have it arrive at the same time as the foot. This allows the hand to retain its freedom, to speed up or change direction if and when necessary.” Hand then goes on to say that, “It is the way that everyone naturally attacks if you put a sword in their hand and ask them to make an attack on a pass.” [10]

This is a central part of Hand’s take on Silver’s True Times, and is referred to as the “Slow Hand.” The way Hand approaches this is as follows: You first move your hand to bring the sword before you, and then move it at a pace that would have your strike land just as your foot does. The hand, being slowed relative to its potential speed, is thereby free to defend against any attempts by your opponent to interrupt your attack, or to change the target of your strike based on the movements or openings of your opponent. The “Slow Hand” also presents a threat as you close distance, a threat to which your opponent in theory must respond. This is part of what keeps you safe while you attack.

This seems to align with the following quote from Silver:

“The true fights be these: whatsoever is done with the hand before the foot or feet is true fight. The false fights are these: whatsoever is done with the foot or feet before the hand, is false…” -Paradoxes of Defence, 14

Silver then provides a description of relative speeds of different parts of the body, categorizing their usage into the True and False times, stating that the Time of the Hand is the first True Time, followed by the Time of the Hand and Body, followed by the Time of the Hand, Body and Foot and the Time of the Hand, Body and Feet (these are described in greater detail later in this article). Hand takes this description of True Times, along with the above quote, to mean that “whatsoever” is done with the hand before the foot is true, and whatsoever is done with the foot before the hand is false. Therefore, according to Hand, it is okay to close distance with an attack, as long as the hand is the first thing to move. This also seems to align with Silver’s advice to close distance under a guard, as the “slow hand” acts as a defense while closing distance, being able to ward off any incoming strikes.

❖

Part Two: Our Alternative Interpretation of the True Fight of George Silver

A Brief Summary of Silver’s Tactics According to Our Interpretation

“…the hand is the swiftest motion, the foot is the slowest, without distance the hand is tied to the motion of the feet, whereby the time of the hand is made as slow as the foot, because whereby we redeem every time lost upon his coming in by the slow motion of the foot & have time thereby to judge, when & how he can perform any action whatsoever, and so have we the time of the hand to the time of the feet.” – G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

Before we go into any great detail about Silver’s tactics and his approach to fencing, we will present this summary of our take on Silver’s system. Our goal is to make it as concise and accessible as possible. Then, once you understand our interpretation of Silver’s True Fight, we can go into the details and support our explanation with Silver’s own words.

The most succinct way to present our understanding of Silver is as follows:

Do not close distance with a step as you attack, because that takes too much time and gives your adversary too much of an opportunity to either parry or strike you as you come into range. Instead, either close distance using Silver’s suggested methods (detailed later) and then attack when you can strike without then having to step, or take advantage of your adversary’s mistakes, such as their stepping into range with an attack or defense (either by waiting for or compelling them to do so).

Silver’s “Tempo”

“…although the unskillful is the first mover, & entered into his action, whether it is blow or thrust, yet the shortness of the true times make at the pleasure of the skillful a just meeting together. In the perfect fight two never strike or thrust together, because they never suffer place nor time to perform it.” – G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

Silver’s terminology is largely congruent with Aristotelian physics, which despite being wholly abandoned in the modern era, were accepted as being true in Silver’s time and would be included in a comprehensive education of someone living in that period. Thus the definitions of the words Silver commonly uses may not quite align with a modern reader’s understanding of language.

Aristotle conceived of time as the quantification for the process of change in an action, categorized in terms of how long the process takes [11], meaning that time was measured by motion. Silver’s use of the word “time” (e.g. Time of the Hand, Time of the Foot) therefore conforms to Aristotelian physics and refers to motion. Understanding this, we see that the Time of the Hand, for example, refers to the movement of the hand from one place to another. It is important to understand that for Silver, “time” has a similar meaning as the word “tempo” as it is used in Italian sources (though not exactly the same), so the time of the hand could be described as the tempo of the hand and the time of the foot as the tempo of the foot.

Some researchers, such as Rafael Ramos da Costa, suggest that Silver was actually based on proto-Newtonian (Galilean) physics, and that Aristotle’s works don’t play a part in how he conceptualized motion and time. This may indeed be so, but ultimately doesn’t change the meaning of what Silver wrote. It is our contention that someone of Silver’s time would have based his writings on his own understanding of fencing, falling back on his education only for terminology. For the purpose of describing fencing times, whether he used Arisotelian terms or Galilean terms doesn’t actually change the meaning. Both Aristotle and Galileo had the notion of one thing being faster than another and that motion consisted of moving from one place to another. Thus two things could cover the same distance with one of them taking less time to do so (being faster) than the other.

Time and Place

“When you attempt to win the place, do it upon guard, remembering your governors, but when he presses upon you & gains you the place, then strike or thrust at him in his coming in.” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

George Silver’s method is relatively simple in theory, though difficult to describe in writing or master in practice. Simply put, the main idea behind Silver’s method is that, if you must step with your attack (must close distance with a step in order to reach your target), then you are not able to hit as quickly as you would have been able to if you did not have to step. Therefore, in order to out-time your adversary, which is a safe way to hit them without being hit yourself [12], you must come close enough to reach them before you actually begin your attack, after which you may deliver an attack without being slowed by having to close distance. Silver calls this distance “the Place”, which denotes the range where you may hit your adversary without having to take a step to close with them [13].

To explain some of the key principles involved in his method of fencing, Silver developed the lexicon of the True Times [14], a list of movements distinguished by the short time involved in making them, in which the hand is always allowed to move freely and at its full potential speed. They do not describe the order in which to begin an action (all motions should usually be initiated at the same time), but instead the entirety of an action itself, performed in a way that ultimately does not encumber the hand. Thus each “Time” remains “True” to itself, that is, to its maximum potential speed.

The True Times are these:

- The Time of the Hand

- The Time of the Hand and the Body

- The Time of the Hand, Body, and Foot

- The Time of the Hand, Body, and Feet

These True Times represent either the movement of the hand alone, or a movement of the hand in combination with other body parts (body, foot or feet), in which the hand is not slowed by the slower movement of the others. This can be accomplished either by moving the hand independently of other body parts and thereby not slowing it (switching feet in place, or a step that lands after the strike does), or by shortening the time of the step or lean so that it fits within the time of the hand (this can only be accomplished with a very small step or a very small lean). Since the hand is much faster than the body or feet, neither of these methods can be used to close distance, and so they cannot be used if you cannot already reach your target.

The reverse order (Feet, Foot, Body, and Hand) are known as the False Times [14]. These times are either steps into your opponent’s reach without any other action, or require the hand to be slowed or to hesitate while the body, foot or feet attempt to close distance with the opponent. Thus the fastest Time of the Hand is tied to the slowest Times of the Foot or Feet, rendering these times False. Someone who moves in False Times is therefore slower than someone who moves in True Times, which results in an ineffective and dangerous strategy. Speaking of this, Silver states:

“But the skillful man can most certainly strike and thrust just with the unskillful, because the unskillful fights upon false times, which being too long to answer the true times, the skillful fighting upon the true times, although the unskillful is the first mover, & entered into his action, whether it is blow or thrust, yet the shortness of the true times make at the pleasure of the skillful a just meeting together.” – Paradoxes of Defence, 7

Actions in True Times may only be performed at the proper distance, at which the hand can reach the target without being slowed by the motions of the feet or body, the Judgment of which is foundational for Silver’s method. Any action which is performed more slowly than the potential/untethered speed of the hand due its initiation at an improperly wide distance is False.

A further explanation of the True Times follows:

- The hand (and arm), which holds the sword, is the part of the body that is able to be moved most quickly when acting independently. It may only do this when in range to hit the adversary or another target (such as his sword) without having to be accompanied by a step, a position called the Place.

- The body, by leaning forward or backward, is not able to be moved as quickly as the hand due to its greater mass, and the fact that it carries the hand with it.

- The foot (or feet), in stepping forward or backward in order to close or create distance, is the slowest mover, since it carries the body and hand with it, resulting in its movement of the greatest mass.

When a person is already in the Place where they may hit their adversary by moving their hand alone (their fastest time), being unencumbered by their body or foot, they are free to do this without delay because they are already close enough to do so. If instead they must move their foot and body into the place while they are executing their attack, then they must necessarily tie their hand to their foot [15], either by waiting until their step brings them to the Place in order to deliver an attack with the hand, or by artificially slowing down their hand in order to wait for their body and foot to catch up to it. Therefore:

- If they simply step forward to come to the Place in order to deliver an attack with the hand, then they are greatly exposing themselves, since they are leading with their foot and body before their hand and sword have occupied their adversary’s sword or otherwise acted to keep themselves safe. This is a False Time, tying the swift Time of the Hand to the slow Time of the Foot.

- If they artificially slow down their hand in order to wait for their body and foot to catch up to it, then their attack is slow and weak, easily warded or counter-attacked. This is a False Time, tying the Hand to the Time of the Foot.

- If they attempt to use the Time of the Hand to strike at full potential speed without having yet attained the Place of their target, then their strike will fall short, since being the quickest and beginning first, the hand will have finished its motion (and thus the strike’s arc) before the body and foot are able to come into distance to hit the intended target. This would be a True Time, except that it was used at an incorrect distance (outside of the Place), resulting in a miss with the attack and the creation of an opening in the attacker which the adversary may exploit, since now The Place has been gained for them.

The only steps that Silver explicitly allows when you have the Place of your adversary are those that have you “tread your ground in course to strike,” [16] by which he means a switch-step, in which your feet change position in place without closing distance, or a similar action with the feet in which the body does not drastically change position (such as stepping back while striking). Taking such a step with an attack while having the Place of the adversary fits into Silver’s description of True Times because it does not slow the hand, since the hand does not have to wait for the feet to complete their motion because of “your hand & foot being then of equal agility.” [16]

Any actual attack begun from outside of the Place is by definition one made in a False Time. Thus, it is only after having come to the Place that the hand is free to move at its quickest, being unfettered by the body and foot’s need to close distance. Once the Place is reached, we are told that the hand is able to be moved more quickly than the eye may follow, and therefore is able to freely strike any opening on the adversary, which they may not defend because their eye does not have the time to discern the target of the hand’s swift motion [17]. After having hit the adversary in the Time of the Hand, Silver’s universal advice is then to Fly Out or Back from the Place, because to remain at such a distance where the adversary may quickly strike you in the Time of the Hand is extremely dangerous, since you may not reliably defend yourself [18].

It is important to understand that Silver’s description of True Times only applies to actions that involve the Place. For example, an action that is executed when you are in the Place to hit your target, or an action during which you can gain your adversary the Place (put yourself in range of your opponent’s time of the hand). This is similar to how tempo is viewed by the Italians, as there is no tempo outside of opportunity [19]. So an attack itself, which should only happen when you have the Place of your adversary is an action that must adhere to the True Times. For example, if you step into range of your adversary without having first neutralized their weapon, then you are committing a false time action. If you just step outside of your adversary’s range, that exact action is neither true nor false, as the True Times do not apply.

Sometimes, the True Times apply to actions that win you the Place, but sometimes they don’t. The determining factor is whether you are potentially gaining the adversary the Place of you by doing so (if your action would put you into their reach).

There are two possible ways in which you may attain the Place against your adversary. The first and most common method is when the adversary steps into distance for you to use the Time of the Hand against them (they gain you the Place). The second method is for you to safely close distance with your adversary, using the True Times, before you attack them in the Place (you win the Place) [12].

It is well beyond the scope of this or any article to provide a detailed look into the specific methods Silver uses to attain the Place, as that would encompass essentially his entire system–that would take one or more books to do properly. However, we will provide an outline and brief examples in the following sections.

You Cannot Have The Place if Your Adversary Also Has The Place

“…because through judgement, you keep your distance, through distance you take your time, through time you safely win or gain the place of your adversary, the place being won or gained you have time safely either to strike, thrust, ward, close, grip, slip or go back, in which time your enemy is disappointed to hurt you, or to defend himself, by reason that he has lost his place…”

– G. Silver, Brief Instructions

One of the most important components of Silver’s concept of the Place is that you should not attempt to win the Place of your adversary, nor allow your adversary to gain you the Place, if your adversary also has or will have the Place of you. Not that this cannot happen–Silver acknowledges this and warns against it [20]–but rather, you must not allow it to happen. Therefore, it is not enough merely to step within range of your adversary, but the adversary must be doing something in that moment, either through their own mistake or because you compelled them, that occupies their sword and renders them unable to act against you in time.

An example of this is when the opponent steps in with an attack in False Times. Silver advises that you slide back slightly as they do so, depriving them of the Place, and strike their arm. Since they have already launched a committed attack, their forearm will be in range (you will have the Place of their forearm) whereas you, standing just out of reach in Open Fight (sword held high, point up) or in True Guardant, will be completely out of reach. Their committed attack occupies their sword and gives you the opportunity to strike their forearm. Technically, as you strike, you will bring your forearm into their range, but their weapon is not in a position to act upon it (their arm being “spent”), therefore you have the Place and they do not.

Although this example applies only to a particular scenario, this principle must be in play in every action involving the Place, or the fight is not true.

The Adversary Gains You The Place

“…be sure to keep your distance, so that neither head, arms, hands, body, nor legs be within his reach, but that he must first of necessity put in his foot or feet, at which time you have the choice of 3 actions by which you may endanger him & go free yourself.” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

In order for your adversary to be able to reach you, they must come into the range where you may also reach them (assuming that your stature and weapons are equal). If they do this by stepping either with an attack or by simply coming in, and thus moving in False Times, you are given an opportunity to safely hit them, if you utilize True Times as Silver advocates.

Examples of how to act in True Times when the adversary gains you the Place of them (they step into distance where you may hit them with the Time of the Hand alone), make up the majority of Silver’s method, and include the Three Actions, namely attacks (and counterattacks), wards (parries), and slips (voids) [21]; any of which you may perform against them when they come in. Note that in each of these actions, the adversary’s sword is preoccupied, either by your sword or by a committed motion that leaves you safe, and therefore they are unable to use the Time of the Hand against you; leaving you in danger only if you hesitate or move in a False Time. None of these listed actions require a step to alter distance if performed with the appropriate timing and at the right range (the Place), but any of them may be accompanied by a movement of the body and/or foot or feet, as long as those movements do not slow down and hinder the hand.

In other words, True Times must always be observed in each of these Three Actions, as follows:

- To use True Times with attacks (when the adversary gains you the Place), keep your distance until your adversary enters with a False Time (steps towards you with an attack, or alternatively in a defensive position), thus gaining you the Place of them. As they do so, you may either:

- If they attack, then strike or thrust their arm before their attack would land by using the Time of the Hand while Flying Back with the Body, and Foot or Feet, achieving a safe distance; or strike their head with a downright blow in the Time of the Hand just as they would strike you, simultaneously crossing their sword to defend yourself while slipping back a bit to create space and then fly back.

- If they close in Guardant (a non-threatening, defensive hanging position) then strike or thrust their openings with the Time of the Hand, and then Fly Back with the Time of the Body and Foot or Feet.

- If they attack, then strike or thrust their arm before their attack would land by using the Time of the Hand while Flying Back with the Body, and Foot or Feet, achieving a safe distance; or strike their head with a downright blow in the Time of the Hand just as they would strike you, simultaneously crossing their sword to defend yourself while slipping back a bit to create space and then fly back.

- To use True Times with wards (when the adversary gains you the Place of them), keep your distance until your adversary enters with a False Time (steps towards you with an attack), thus gaining you the Place. As they do so, you may ward and immediately after counterattack to one of several targets on their body, using the Time of the Hand, and then Fly Out with the Time of the Body and Foot or Feet.

- To use True Times with slips (when the adversary gains you the Place of them), keep your distance until your adversary enters with a False Time (steps towards you with an attack), thus gaining you the Place. As they do so, you may slip (void) their strike, removing whatever part they are targeting, and counterattack after them with the Time of the Hand, and then Fly Back with the Time of the Body and Foot or Feet.

Although examples of the adversary gaining you the Place are much more prevalent in Silver’s works than are those of you winning the Place, the main point of contention between the old interpretation and the one presented in this article lies in the understanding of the latter, and therefore we will leave the current subject of the Place being gained for you, and move on to detailing our understanding of how to win the Place of your adversary.

You Win The Place of Your Adversary

“Know what the place is, when one may strike or thrust home without putting in of his foot.” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

Let us now examine how to win the Place of the adversary (close distance with them). It is important to note that examples of these instances are much rarer in Silver’s method than those in which the adversary gains you the place (as discussed in the previous section).

All of the ways that Silver tells us how we may win the Place of the adversary may be categorized into four groups:

- Close distance under guard, thereby not committing to any False Time attack which would expose you to danger, but remain ready to defend yourself as you enter the Place.

- Be able to reach them without them being able to reach you, either due to your natural height advantage or your use of longer weapons, or by their over-extension of their body parts.

- Preoccupy their weapon by making an indirection (pushing or striking their blade aside) if their sword is extended [22], and therewith step into the Place.

- Use a false or feint in order to induce them to attempt to ward [23]. Along with this false, your body and foot may be brought forward into the proper distance to then attack the adversary.

Silver includes four clear examples in his writings that describe winning the Place with his exemplary weapon, the short sword. Summaries of these four examples follow:

- You may press in and cross their sword in True Guardant when they are also in True Guardant (hanging guard), and then immediately upon winning the Place either strike their head or thrust their stomach, and then fly out. [24]

- You may cautiously cross their point when they hold their sword above their head with their point directed toward you (Imbrocata), then put it aside strongly and immediately strike or thrust them, and fly out. [25]

- If they stand with a wide stance and their forward knee quite bent, then come to where you have the Place of their knee, which you may then safely strike in the Time of the Hand, and fly back. [26]

- If you ascertain that your adversary cannot effectively strike from their ward (riposte from their parry), then you may double (remise) and false (feint) against them, winning the Place against them with these deceits. But if they are skillful it would be too dangerous to attempt such tactics. [27]

Additionally, winning the Place is described in the use of other weapons by Silver. Summaries of these entries follow:

- Against an adversary with rapier and dagger, make attacks with your sword to their dagger hand until you come to where you may cross their rapier blade, then strike or bear their point aside and strike or thrust them, then fly back. [28, 29]

- Against one in open or true guardant with rapier and dagger, then from one of the same fights you come in and cross their sword guardant and then thrust at their stomach and fly out; but if they defend, then strike them on the head while flying out. [30]

- With the two hand sword or short staff, against an adversary who always keeps two hands on the grip you win the Place by keeping your distance and thrusting at them while releasing one hand from your weapon, thus safely outreaching them. [31]

Silver also discusses winning the Place in Paradoxes of Defense:

- A tall person may have the Place of a shorter person although the latter may not reach them, due to their differences in reach. [32]

- If when two people fight with rapiers and poniards, if one or both press in to win the Place, the first to thrust will hit their adversary, and if both thrust together they will both be hurt or slain. [20]

We can see by the previous examples that Silver only begins his actual attack once the Place is won, after having exploited whatever advantages he may, or by taking whatever preparatory actions are necessary in order to reach the Place safely through the use of the True Times.

A Summary of Silver’s Method According to Our Interpretation

“…the time of the hand to the time of the foot, which fight being truly handled is invincible advantage.” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

Silver’s tactics can be summarized as the implementation of his Four Grounds or Principles, namely, Judgement, Distance, Time and Place [33]. Through your understanding of the True Times you develop your Judgement, which is your ability to discern how and when to apply these concepts as they are necessary in the management of Distance.

Distance is the amount of space that exists between you and your adversary, and should be managed in a way that allows you to take advantage of your adversary by fighting them in the correct Time.

Time is the motion of a body from one point of rest to another, the application of which, at a certain distance, being achieved by utilizing the True Times, allows you to gain an advantage over your adversary, a position known as the Place.

The Place is the position whereby you may reach your adversary by moving the hand alone, without having to move the foot in order to close distance, and is achieved safely only by the correct use of Judgement, Distance and Time.

Once in the True Place, because you are able to act in the swiftest Time, that of the Hand (as opposed to an adversary’s slower time), and because you have arrived there with the advantage that disallows the adversary from using their own Time of the Hand (as is detailed in all of the techniques that Silver describes) you are safe to offend them as you see fit, but only for a brief moment, before your advantage is lost. After acting in the brief moment of safety you have achieved by attaining the True Place by utilizing the True Times, you must then Fly Out or Back, taking Time to once again create Distance between yourself and your adversary, from where you may then once again use your Judgement in order to achieve the Place once more, if need be.

We can see by these principles and the previously detailed examples that Silver describes a complete art, one with a clear emphasis on tactics which minimize risk in order to allow a practitioner to come through conflicts most safely.

❖

Part Three: A Refutation

of the Old Interpretation

In this section, we will examine why we believe the established interpretation is incorrect by using comparisons to other arts, Eastern and Western, and also by isolating the ideas present therein that we think were erroneously imported or misinterpreted.

First and foremost, we wish to emphatically state that we are not in any way claiming that Stephen Hand’s (and those who follow his teachings) method of fencing is in any way wrong or ineffective–that is not the purpose of our article or our alternative interpretation. The only claim that we are making is that the established interpretation does not conform to Silver’s writings, neither his theories nor his examples. It is important to note that many of the principles of the established interpretation are largely similar to those of Classical Fencing, and therefore as a method of fencing it is strongly supported.

To go beyond the established interpretation’s understanding, one has to delve deep into Silver’s ideas and examples. Only a comprehensive understanding of Silver can make the full breadth of his system and concepts apparent, and once that happens, the established interpretation becomes indefensible.

Universality of Theory

“To prove this, I have set forth these my Paradoxes, different I confess from the main current of our outlandish teachers, but agreeing I am well assured to the truth, and tending as I hope to the honor of our English nation.” – G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

One of the pillars upon which the established interpretation is based is the assumption that since it aligns with modern fencing theory (which evolved from Classical Fencing and ultimately from Italian fencing) it is therefore universal. This idea lends that interpretation credence, since something that is universal to all fighting systems is more likely to be correct. There are two problems with this. The first is that Italian fencing is the very thing Silver is criticizing, and the second is that Italian fencing is not actually limited to using time in the way that the established interpretation advocates.

Vincentio Saviolo, the recipient of the brunt of Silver’s censure, has little to say explicitly on the subject of time. He writes in His Practise, In Two Books (1595) that “they may learne the just time and measure, and make the foote, hand and body readily agree together, and understand the way to give the stoccata and imbroccata right…“

On the conceptualization of time itself he simply states: “…some hold that there are foure times, other five, and some six, and for mine own parte, I thinke there are many times not requisite to be spoken of, therfore when you finde your enemye in the time and measure before taught, then offer the stoccata, for that is the time when your enemie will charge you in advancing his foot, and when he offereth a direct stoccata, in lifting or moving his hand, then is the time…“

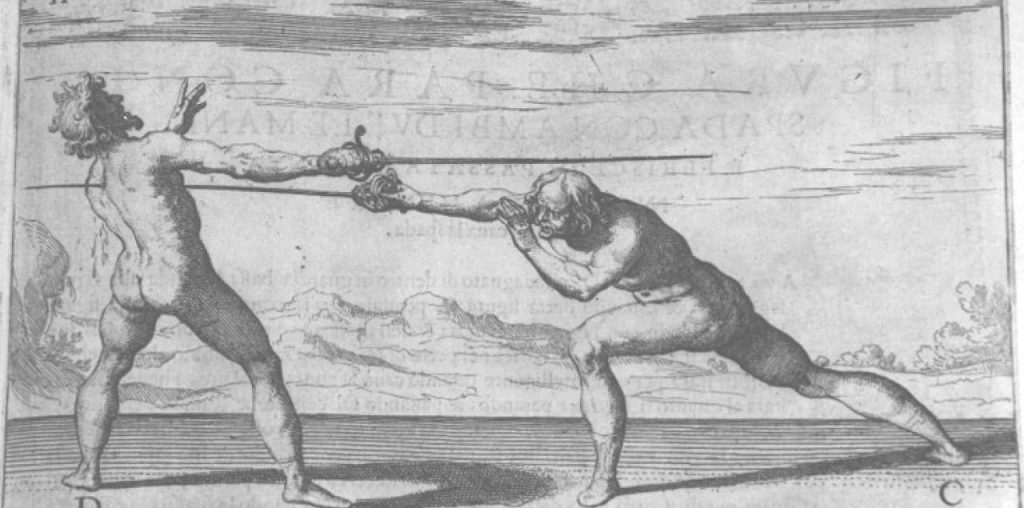

Salvator Fabris is more detailed in his conceptualization and utilization of time. His approach to the fight is that he either creates or waits for specific circumstances that make executing attacks safe, such as cautiously advancing into range (the Place) before launching an attack. Fabris does not say that merely by moving your sword/arm first as you close distance with a step to attack that you are made safe, nor does he recommend attacking in this way; in fact, he specifically advises against doing this, recommending stepping into close distance first, before bringing the body into range [34]. The key difference between Fabris’s approach and Silver’s is that Silver would consider some of his actions, those that do not adhere to the True Times as we understand them, as too risky.

Ridolfo Capoferro approaches some of the principles of the fight in a similar way as Silver, but with notable exceptions, one of the largest being that when the adversary is reacting to your pressure/provocations (“Obedienza” in Italian Fencing or “Zwingen” in Liechtenauer’s Kunst des Fechtens), an Italian fencer in Capoferro’s style might consider this to be appropriate opportunity to lunge (step with an attack) [35]. Here we see a similar understanding of time and distance and the risks of stepping to close distance with an attack, but two different degrees of caution applied to the solution.

Silver seems to be considerably more cautious than those Italian masters of his time with whose methods he was familiar. His dislike of these Italian methods was seemingly based on a very few specific qualities of their approach, their dangerous manner of attacking (in his view), and their general use of False Times instead of True Times. When it comes to foundational principles alone, Silver’s fight, as we interpret it, was otherwise somewhat similar to that of the Italians, but with a very different emphasis, that being defense rather than offense. However, certain other key differences matter a great deal as well. Specific techniques, physical applications of principles, body mechanics, weapons, guards, posture and so on were quite different between these methods, despite being based on largely the same foundations. To reiterate, Silver’s primary criticism of the Italians is their greater acceptance of risk, which he believed led to both parties in a duel often dying of their wounds [36].

Western Boxing is another martial activity where stepping in before attacking is commonplace. An analysis conducted by the authors of over one hundred boxing matches revealed that the overwhelming number of punches were thrown without a step of any kind. A fairly high number were thrown with a tiny step that did not slow the punch or alter the distance (most likely to increase the impact force or to realign the body). A very few punches (relatively speaking) were thrown with a larger step, and in a great many of these, the person doing the stepping was punched in the face as they came into range (the opponent responded to a longer time/tempo with a shorter one) even though their fist was thrust out in front of them.

Moving on to non-European styles, Japanese sword arts, such Battodo, Kenjutsu and Iaido (but not quite Kendo) approach the fight in much the same way as Silver, according to our interpretation, though practitioners of Japanese arts do not speak of or conceptualize things the same way that HEMA practitioners do. For example, “striking with a step” means something fundamentally different depending on which of the two you speak to. When asked about stepping with the cut, Sang Kim Sensei of Byakokkan Dojo said, “Yes [you start your step first, or take a small step], unless you’re in range already, then you don’t need to step. But you never want it where the sword moves first and your body lags behind [because you attack from too great a range]. That’s when you get parried or your opponent can cut through you.” [37] Additionally, as far as Eastern Martial Arts go, Kali and Silat are both disciplines that primarily call for stepping into distance first and then attacking.

It is important at this point to note that when the advice to “step first and then strike” is brought up, it generally conjures images of someone foolishly stepping into distance (perhaps with “their guard down”) and thereby getting hit by their adversary. This could not be further from how these various arts address the management of distance. Approaches vary in preference more than fundamentally, meaning that all arts use pressure (feints, exposing fake vulnerabilities, projecting psychological threat, etc.) and wards or indirections (battering aside, crossing) to close distance, but some may greatly prefer one to the other. Regardless, in none of the above arts, nor in our understanding of Silver, does one merely step into distance without seeing to their own safety. Silver calls for the use of Judgement to manage distance, through which your greater understanding (of True Times vs. False) allows you to make better decisions about which methods and tactics to use to close distance.

As far as the hand moving first in an attack sequence being universal among all martial arts (or close to it), this may indeed be prevalent when thrusting, for both biomechanical and tactical reasons. However, this is not always or even usually true of cuts. Although we believe the established interpretation is built at least in part by relying on this one aspect of Italian (and other) fencing systems, this has little to do with Silver’s True Times.

Erroneously Imported Concepts

‘…it grew to a common speech among the countrymen “Bring me to a fencer, I will bring him out of his fence tricks with down right blows. I will make him forget his fence tricks, I will warrant him.”‘ -G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

The act of safely bridging distance in order to offend the adversary has troubled practitioners since the inception of modern Historical European Martial Arts, much as it probably had the progenitors of the ancient arts they study. While the authors have already presented our understanding of how Silver actually describes the process of doing this, it may be helpful to point out what solutions to this problem were mistakenly grafted onto his art by the practitioners of the established interpretation, as well as their origins. The established interpretation makes use of three main concepts in order to “safely” bridge distance with an attack.

The first concept to be mistakenly imported into Silver’s method is that of using a threat to keep one safe while attacking. The theory behind this states that the adversary must address your attack in order to protect themselves, thereby dissuading them from attacking you. Such a strategy can be seen in such instances as the use of Zwingen in the Kunst des Fechtens, but Silver describes no such thing with any real attack, only mentioning it when describing Falses (feints), which he prefers not to use except in specific circumstances [23]. Simply assuming that an adversary will “do the right thing” by defending themselves instead of attacking you is a recipe for a double-hit, and is to be avoided.

The second of these erroneous imports is often paired with the first, being the idea that, with an attack, the sword must cross distance ahead of the body in order to create a path of safety through which the body may follow by means of an advancing step. In other words, the sword becomes a shield by closing the line of attack in order to allow one to close distance safely. In Silver’s method using the sword to protect the body is evident enough when it comes to wards (parries) that make a true cross, secure interceptions with the fort of the blade or basket of the hilt , but this concept is only advocated in one situation when it comes to (counter)attacks [38], and it is never once described as being used during any actual attack by one acting as the Agent. This concept is, however, found in such arts as the Kunst des Fechtens, where it is applied as part of the “Vier Versetzen” (Zwerchhau to break the guard Vom Tag [39]), and in later styles such as Charles Roworth’s, where it was a general rule while attacking with a cut while using the Saber or Broadsword [40]. Silver repeatedly rejects the idea of closing distance with a step while actually attacking, as has been demonstrated, and never offers any exception.

The third foreign concept to be erroneously added to Silver’s method, and the one that most egregiously violates his rules, is that of the “Slow Hand”, this being used to allow for extra time to defend or change target while initially closing-in with an attack. This concept is the very definition of a False Time [14], which ties the swiftest Time of the Hand to the slow Time of the Foot [41], and is therefore outright rejected by Silver as being neither safe, advantageous, nor advisable. Since distance is being closed by the Agent with an attack itself, the attack is delivered in the Time of the Foot, which is always defeated with the Time of the Hand, regardless of the particular actions involved [42]. The most important point is that Silver never actually describes such actions as changing an attack into a defense, or another attack, anywhere in his writings, nor does he imply them. Furthermore, his method according to our interpretation does not in any way require such additional tactics in order to be viable, as we have demonstrated.

Aspects of the application of this concept of the “slow hand” are similar to what is known as a “compound attack” in Classical Fencing, though its execution may be somewhat different. The term “slow hand” itself does appear once throughout all of Silver’s works, in the Additional Notes [43], but no thorough explanation of its meaning is included, nor is any such tactical advice suggested regarding it. The authors suggest that such an interpretation as the “slow hand” came about in order to fill-out and lend validation to the otherwise nonexistent (in Silver’s method) tactic of actually attacking an adversary by closing distance, something which the advocates of the old interpretation feel is otherwise crucially missing from, but as we have demonstrated is indeed not only unnecessary, but anathema to, the True Fight.

Misinterpretation of the Text

“There is nothing permanent that is not true, what can be true that is uncertain? How can that be certain, that stands upon uncertain grounds?” – G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

Silver states that “whatsoever” is done with the hand before the foot (and so on) is true and what is done with the foot before the hand is false [15]. The established interpretation relies heavily upon this and assumes that it is absolute, but to assume that “whatsoever” is to be taken entirely literally leads to erroneous conclusions. For example, when through judgment you decide your adversary is doing something you don’t like and you want to keep your distance, and so you step back [18], must your hand move before your foot? What about if you are twenty feet from your adversary and you want to walk closer, must your hand commit an arbitrary motion before each and every step? We do not actually think that those who uphold the established interpretation would agree with any of these absurd scenarios. Our point is that when you consider these examples, it immediately becomes obvious that “whatsoever” does not actually mean “whatsoever,” but is applied only in a specific context.

Furthermore, Silver himself clearly gives an example of an action done with the foot first, completely removing the possibility that “whatsoever” literally means whatsoever:

“But ever remember that in the first motion of your adversary towards you, that you slide a little back so shall you be prepared in due time to perform any of the 3 actions aforesaid by disappointing him of his true place whereby you shall safely defend yourself & endanger him.” – Brief Instructions, Cap. 2, 2

So, what does Silver mean when he says that whatsoever is done with the hand before the foot is True and whatsoever is done with the foot before the hand is False? As previously discussed, the True Times only apply to actions either in the Place or actions that could put you in the place of your adversary, and that is what Silver is describing when he says “whatsoever.” That is the necessary context. All such actions must be initiated with the hand in order for them to be True, because any such action initiated with the foot or body would by definition slow the hand by making it hesitate while those other parts begin moving. Therefore, in such a motion, the hand is not free to move at its fastest speed, and since these actions involve the Place, that means you can be struck by your opponent. Generally speaking, any such action would have to be properly executed with either the hand alone (so as not to put yourself into the Place of your adversary while stepping) or with the foot only moving once the hand has accomplished its objective (e.g. removing your adversary’s sword from a position in which it could threaten/harm you). Thus, in this context, “whatsoever” is done with the hand before the foot is True, and “whatsoever” is done with the foot before the hand is False.

Conclusion

“…there is but one truth in all things, which I wish very heartily were taught and practiced here among us, and that those imperfect and murderous kind of false fights might be by them abolished.” – G. Silver, Brief Instructions

It has been demonstrated throughout this article that Silver’s method expressly forbids stepping to close distance with attacks when doing so is necessary in order to reach the adversary, because this ties the swift Time of the Hand to the slow Time of the Foot, since the foot must carry the body and hand forward to come into range of the target. Instead, actions following the True Times must first bring you safely to the Place, from which you may swiftly attack your adversary in the Time of the Hand, before retreating again to a safe distance.

If the established theory were correct, then it would stand to reason that Silver would include at least one example of advice to attack with a step in the manner advocated by this interpretation, but he does not–not a single example of this can be found anywhere in his writing, except as mistakes by the adversary to be taken advantage of. Such an action is anathema to Silver’s conceptualization of proper fencing.

The established interpretation is held by adherents to be inherent in every Martial Art, but this is certainly not the case; nor is it with our alternative interpretation. What is inherent in every Martial Art are the same laws of physics which govern all distance and time, something which Silver clearly had keen insight into, allowing him to develop a method of fencing that would allow its practitioners, if they perfectly followed it, to stay safe in the fight [44], which was Silver’s greatest concern during the illicit dueling craze of his time that left so many of his countrymen injured or dead [45].

We hope that in writing this article we have made it clear that we believe that Silver’s method, though not universally applied, grants the fencer who acquaints themselves with it greater knowledge of how timing in fencing may be understood, and provides them with an opportunity to learn about a unique and excellent Science of Defense.

Special thanks to Rafael Ramos da Costa, Vincent Le Chevalier, Matt Galas, Shanee Nishry, David Rowe, Betsy Winslow, Sang Kim, Myles Cupp, David and Dori Coblentz, Henri De La Garde, Reinier Van Noort, James Reilly, Jake Norwood, Sean Franklin, and Stephen Hand.

Citations

“And because I know such strange opinions had need of stout defence…” -G. Silver, Paradoxes of Defence

I much enjoyed reading this article and it is certainly helpful in making sense of the “dark riddle” which is Silver’s work! Silver wrote many pages of theory in Paradoxes and both theory and practice in Bref Instructions. With a bit of patience interpreting his archaic modern English, there is plenty of information written by him for us to reconstruct what it was he wanted us to learn from him.

The True Times are the order of what moves fastest and what moves first in what order, thus the hand alone is faster than the hand with a lean, the hand with a lean is faster than the hand with a lean and a step with one foot (a lunge), and the hand with a lean and lunge is faster than an attack with the hand, a lean and two steps like a fleche or any attack using more than one step. Thus the Patient is always at an advantage since he can hit first as the Agent is moving into striking range as the Patient doesn’t have to move his feet very far compared with the Agent.

I totally agree that being in Place to offer an attack purely in the Time of the Hand is the most perfect of attacks in Silver’s system, but it is not the only True Time. Even the attack of the Hand, Body and Feet is still a True Time. Thus the “slow hand” attack is still a true time, but In Bref Instructions 5.4 Silver warns us against using this kind of feint against a stationary opponent since a skilled opponent will be able to react in time against it and hit you. The “slow hand” is thus the worst of the True Times, albeit a true time.

Silver, as rightly pointed out in this article, absolutely does advocate moving your feet in defence. You are to step back a little against every attack made against you, which makes you a less certain target and gets you a bit out of range. The movement of your feet is covering less distance than the movement of his feet while he attacks meaning that you are taking less time in your movement of your feet than he is taking in his attack, and so you are at leisure to hit him before he can hit you. Silver also advocates moving the back foot circularly away from the incoming attack if you are parrying his attack. I assume if you are not parrying but rather hitting him (often on his hand) as you are slipping back then you need not move the back foot circularly away, you just slip yourself straight back.

Silver believes that two experts will not be able to hurt each other. The reason is that the attacker is always slower than the defender due to the attacker having to break distance with his foot or feet. Neither one will find an opportune moment to attack since both are keeping their guard and distance True.

To get the opponent to make the first move you would have to feign an opening, but Silver does not advocate this at all, making him very different from many other fencing masters. Opening yourself up to a clear vulnerability is inviting assisted suicide, and is thus not a True way to fight. Thus, Silver has no Invitations at all. An expert fencer will realize the danger and not take the bait. Thus, it is a defective tactic – only viable against bad fencers, whom you’ll likely be able to beat anyhow with the True Fight without having to resort to trickery.

If you want to end the fight (and of course you want to) then you need to advance under guard. You can do this against a striker with Guardant ward and by choking up his right arm by moving in towards his right side and then doing what you need to do in the situation whether that be with a parry and riposte, or a cross and attack or a cross and Gripe. Against a thruster you’ll have to use the good ole Rapier-ish stringere-type “Forehand Ward” movements. Either way – with Guardant ward or Forehand ward you need to make a true cross with his sword and now you are into the Close Fight phase where you follow up the cross with a thrust, strike or Gripe.

In the end, the “vantage” lies with the fencer in better command of his Governors, being basically the better sense of distance, timing and technique. He who practices more often will have a better sense of the Governors.